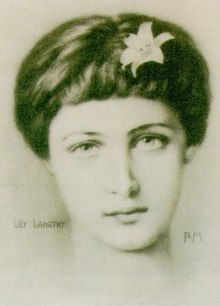

Lillie Langtry

Lillie Langtry | |

|---|---|

Langtry in 1882 | |

| Born | Emilie Charlotte Le Breton 13 October 1853 |

| Died | 12 February 1929 (aged 75) |

| Occupation | Actress |

| Spouses | |

| Children | 1 |

| Signature | |

| |

Emilie Charlotte, Lady de Bathe (née Le Breton, formerly Langtry; 13 October 1853 – 12 February 1929), known as Lillie (or Lily) Langtry and nicknamed "The Jersey Lily", was a British socialite, stage actress and producer.[1]

Born on the island of Jersey, she moved to London in 1876 upon marrying. Her looks and personality attracted interest, commentary, and invitations from artists and society hostesses, and she was celebrated as a young woman of great beauty and charm. During the aesthetic movement in England, she was painted by aesthete artists. In 1882 she became the poster-girl for Pears soap, and thus the first celebrity to endorse a commercial product.[1][2]

In 1881, Langtry became an actress and made her West End debut in the comedy She Stoops to Conquer, causing a sensation in London by becoming the first socialite to appear on stage.[3] She starred in many plays in both the United Kingdom and the United States, including The Lady of Lyons, and Shakespeare's As You Like It. Eventually she ran her own stage production company. In later life she performed "dramatic sketches" in vaudeville. From the mid-1890s until 1919, Langtry lived at Regal Lodge at Newmarket in Suffolk, England. There she maintained a successful horse racing stable. The Lillie Langtry Stakes horse race is named after her.

One of the most glamorous British women of her era, Langtry was the subject of widespread public and media interest. Her acquaintances in London included Oscar Wilde, who encouraged Langtry to pursue acting. She was known for her relationships with royal figures and noblemen, including the future King Edward VII, Lord Shrewsbury, and Prince Louis of Battenberg.

Biography

[edit]

Born in 1853 and known as Lillie from childhood, she was the daughter of the Very Reverend William Corbet Le Breton and his wife, Emilie Davis (née Martin), a recognised beauty.[4] Lillie's parents had eloped to Gretna Green in Scotland, and, in 1842, married at St Luke's Church, Chelsea, London.[5] The couple lived in Southwark, London, before William was offered the post of rector and dean of Jersey. Emilie Charlotte (Lillie) was born at the Old Rectory, St Saviour, on Jersey. She was baptised in St Saviour on 9 November 1853.[6]

Lillie was the sixth of seven children and the only girl. Her brothers were Francis Corbet Le Breton (1843–1872), William Inglis Le Breton (1846–1924), Trevor Alexander Le Breton (1847–1870), Maurice Vavasour Le Breton (1849–1881), Clement Martin Le Breton (10 January 1851 – 1 July 1927), and Reginald Le Breton (1855–1876). Purportedly, one of their ancestors was Richard le Breton, allegedly one of the assassins in 1170 of Thomas Becket.[7]

Lillie's French governess was reputed to have been unable to manage her, so Lillie was educated by her brothers' tutor. This education was of a wider and more solid nature than that typically given to girls at that time.[8] Although their father held the respectable position of Dean of Jersey, he earned an unsavoury reputation as a philanderer, and fathered illegitimate (or natural) children by various of his parishioners. When his wife Emilie finally left him in 1880, he left Jersey.[9]

From Jersey to London

[edit]

On 9 March 1874, 20-year-old Lillie married 26-year-old Irish landowner Edward Langtry (1847–1897), a widower. He had been married to the late Jane Frances Price.[10] Her sister, Elizabeth Ann Price, had married Lillie's brother William.[11]

Lillie and Edward held their wedding reception at The Royal Yacht Hotel in St Helier, Jersey. Langtry was wealthy enough to own a large sailing yacht called Red Gauntlet, and Lillie insisted that he take her away from the Channel Islands.[12] In 1876 they rented an apartment in Eaton Place, Belgravia, London, and early in 1878 they moved to 17 Norfolk Street (now 19 Dunraven Street) off Park Lane to accommodate the growing demands of Lillie's society visitors.[13]

In an interview published in several newspapers (including the Brisbane Herald) in 1882, Lillie Langtry said:

It was through Lord Raneleigh [sic] and the painter Frank Miles that I was first introduced to London society ... I went to London and was brought out by my friends. Among the most enthusiastic of these was Mr Frank Miles, the artist. I learned afterwards that he saw me one evening at the theatre, and tried in vain to discover who I was. He went to his clubs and among his artist friends declaring he had seen a beauty, and he described me to everybody he knew, until one day one of his friends met me and he was duly introduced. Then Mr Miles came and begged me to sit for my portrait. I consented, and when the portrait was finished he sold it to Prince Leopold. From that time I was invited everywhere and made a great deal of by many members of the royal family and nobility. After Frank Miles I sat for portraits to Millais and Burne-Jones and now Frith is putting my face in one of his great pictures.[14]

In 1877 Lillie's brother Clement Le Breton married Alice, an illegitimate daughter of Thomas Heron Jones, 7th Viscount Ranelagh, who was a friend of their father. Following a chance meeting with Lillie in London, Ranelagh invited her to a reception attended by several noted artists at the home of Sir John and Lady Sebright at 23 Lowndes Square, Knightsbridge, which took place on 29 April 1877.[15] Here she attracted notice for her beauty and wit.[16] Langtry was in mourning for her youngest brother, who had been killed in a riding accident, so in contrast to the elaborate clothes of most women in attendance, she wore a simple black dress (which was to become her trademark) and no jewellery.[17] Before the end of the evening, Frank Miles had completed several sketches of her that became very popular on postcards.[18]

Another guest, Sir John Everett Millais, also a Jersey native, eventually painted her portrait. Langtry's nickname, the "Jersey Lily", was taken from the Jersey lily flower (Amaryllis belladonna), a symbol of Jersey. The nickname was popularised by Millais' portrait,[19] entitled A Jersey Lily. (According to tradition, the two Jersey natives spoke Jèrriais to each other during the sittings.) The painting attracted great interest when exhibited at the Royal Academy and had to be roped off to avoid damage by the crowds.[19] Langtry was portrayed holding a Guernsey lily (Nerine sarniensis) in the painting rather than a Jersey lily, as none of the latter was available during the sittings. A friend of Millais, Rupert Potter (father of Beatrix Potter), was a keen amateur photographer and took pictures of Lillie whilst she was visiting Millais in Scotland in 1879.[20] She also sat for Sir Edward Poynter and is depicted in works by Sir Edward Burne-Jones.

Lillie Langtry arrived in the late 1870s, the heyday of "The Professional Beauties". Margot Asquith, the wife of a Prime Minister in the early 20th Century: 'These were the days of the great beauties. London worshipped beauty like the Greeks. Photographs of the Princess of Wales, Mrs. Langtry, Mrs. Cornwallis West, Mrs. Wheeler and Lady Dudley collected crowds in front of shop windows. I have seen great and conventional ladies like old Lady Cadogan and others standing on iron chairs in the Park to see Mrs. Langtry walk past; and whenever Georgiana Lady Dudley drove there were crowds round her carriage when it pulled up, to see this vision of beauty, holding a large holland umbrella over the head of her lifeless husband.'[21] According to Margot Asquith Lillie became the centre of social excitement which excelled the other "Beauties". '“The Jersey Lily” – as Mrs. Langtry was called – had Greek features, a transparent skin, arresting eyes, fair hair, and a firm white throat. She held herself erect, refused to tighten her waist, and to see her walk was if you saw a beautiful hound set upon its feet. It was a day of conspicuous feminine looks and the miniature beauties of to-day would have passed with praise, but without emotion.' Mrs Langtry was new to the public, and photographs of her exhibited in the shop windows made every passerby pause to gaze at them. 'My sister – Chartie Ribblesdale – told me that she had been in a London ballroom were several fashionable ladies had stood upon their chairs to see Mrs. Langtry come into the room. In a shining top-hat, and skin-tight habit, she rode a chestnut thoroughbred of conspicuous action very evening in Rotten Row. Among her adorers were the Prince of Wales, (King Edward) and the present Earl of Lonsdale. One day, when I was riding, I saw Mrs. Langtry – who was accompanied by Lord Lonsdale – pause at the railings in Rotten Row to talk to a man of her acquaintance. I do not know what she could have said to him, but after a brief exchange of words, Lord Lonsdale jumped off his horse, sprang over the railings, and with clenched fists hit Mrs. Langtry’s admirer in the face. Upon this, a free fight ensued, and to the delight of the surprised spectators, Lord Lonsdale knocked his adversary down.'[22]

Daisy Greville, Countess of Warwick, tried to analyse Langtry's success. As a young girl, accompanied by her stepfather, she met Lillie in the studio of Frank Miles.

"In the studio I found the loveliest woman I have ever seen. And how can any words of mine convey that beauty? I may say that she had dewy, violet eyes, a complexion like a peach, and a mass of lovely hair drawn back in a soft knot at the nape of her classic head. But how can words convey the vitality, the glow, the amazing charm, that made this fascinating woman the centre of any group the entered? She was in the freshness of her young beauty that day in the studio. She was poor, and wore a dowdy black dress, but my stepfather lost his heart to her, and invited her there and then to dine with us next evening at Grafton Street. She came, accompanied by an uninterested fat man - Mr. Langtry – whose unnecessary presence took nothing from his wife’s social triumph. The friends we had invited to meet the lovely Lily Langtry were as willingly magnetised by her unique personality as we were. To show how little dress has to do with the effect she produced, I may say that for that evening she wore the same dowdy black dress as on the previous day, merely turned back at the throat and trimmed with a Toby frill of white lisse, as some concession to the custom of evening dress. Soon we had the most beautiful woman of the day down at Easton, and my sisters and myself were her admiring slaves. We taught her to ride on a fat cob, we bought hats on the only milliner’s shop in the country town of Dunmow, and trimmed them for our idol, and my own infatuation, for its was little less, for lovely Lily Langtry continued for many a day... I don’t know who coined the phrase “professional beauty,” and if the phrase has gone out, it may be because to-day there are no women so outstandingly beautiful as some of my contemporise were. I cannot prove it, of course; I can only make the assertion. The average of good looks to-day is much higher, but there is none to equal Lily Langtry."[23]

Theo Aronson, royal biographer and author of a book about King Edward’s three “official mistresses”, has put attention to the changing nature of London high society in the late nineteenth century. According to Aronson Lillie was fortunate in her timing. ‘Society, by the late 1870s, was undergoing a transformation. Until then, the English aristocracy had been an exclusive clan, made up of about ten thousand people who, in turn, belonged to about fifteen hundred families. A title (the older the better) or a long established lineage were two of the qualifications necessary to belong to this select group; a third was the ownership of land… But in the course of the last few years things had begun to change. Much of this was due to the attitude of the Prince of Wales. With his penchant for very rich men – whether they be self-made, Jewish or foreign, or indeed all three – he extended the boundaries of the upper classes beyond the gilded stockade of the landed aristocracy. Business acumen, beauty and, to a lesser extent, brains were becoming enough to get one accepted… It was this opening-up of society that partly explains the ease with which Lillie Langtry was accepted; partly, but not entirely.’[24] Much of Lillie’s success of due to her own particular qualities. ‘For one thing, she was not some brash arriviste. She was, by Victorian standards, a lady. Her husband, whatever his shortcomings, did not do anything so vulgar as work for his living. His grandfather might have been a self-made shipping magnate, but Edward was a gentleman of leisure. Then Lillie herself was the daughter of the Dean of Jersey; and clergymen’s daughters, if not exactly aristocratic, were certainly socially acceptable. In the Victorian hierarchy, clergymen ranked besides the landed gentry…. Her air, despite her vivacity and sensuality, was well-bred: she knew how to conduct herself in public.’[25] Above all, Lillie had in 1877, at the age of twenty-three, the advantage of not only being beautiful but of also having an unusual type of beauty. Here were the looks then in favour with the artistic avant garde…. In the age of Pre-Raphaelites, Lillie Langtry was the Pre-Raphaelite woman personified. Everything – the column of a neck, the square jaw, the well-defined lips, the straight nose, the slate-blue eyes, the pale skin (she was nicknamed Lillie, she tells us, because of her lily-white complexion), even the hair loosely knotted in the nape off the neck – conformed to the artistic ideal of feminine good looks. It was no wonder that so many eminent artists fell over each other in their eagerness to paint her… Yet at the same time, Lillie was not one of the languid, ethereal maidens so beloved of the bohemian brotherhood of the day. Her beauty was brought to life by her vivacity.'[26] Lillie possessed beauty, personal magnetism, a curiosity value and an aura of sensuality with the promise of an almost animal passion. Highly intelligent and erudite, Lillie was also one of the most calculating of women. The particular combination of qualities was behind a meteoric rise to fame.[27]

Lillie Langtry was introduced into a bohemian set of London society, after a year of living a quite obscure life in London with her husband Edward Langtry, when she received an invitation by Sir John and Lady Sebright. In Lady Sebright’s crowded drawing room the aristocratic and artistic world overlapped. In the words of Theo Aronson, ‘For Lillie, it was the ideal springboard.’[28] John Everett Millais, also born in Jersey and the most famous painter in the country, was her table-companion that evening. ‘‘That evening at the Sebrights’ transformed Lillie Langtry’s life. The particular milieu – aesthetic, arty-crafty, unconventional – into which she had just been introduced was always on the outlook for new diversion, new sensations and new faces. And there were few faces as striking as hers. Within a few days the hall table of her Eaton Place apartment was heaped with invitations – to lunch, to dine or to dance. By the end of the month the Langtry’s landlady was grumbling about the number of times she was having to answer the door as yet another liveried footman delivered yet another gilt-edged invitation.’[29] The combination of her beauty, personal magnetism and her curiosity value made Lillie one the best-known faces within weeks after Lady Sebright’s party. John Everett Millais and Frank Miles, far from blind of the opportunities Lillie offered, pictured her. ‘My sketches of Lillie during her first London season,’ wrote Miles twenty years later, ‘earned far more than I’ve ever made on the largest commissions for my most expensive paintings.’ Winning Lillie even wider recognition were her photographic likeness. At a time when photography was a relatively new art and an appreciation of feminine beauty at one of its heights, reproductions of attractive women were being bought by a vast public. The “Professional Beauties”, all members of high society, were photographed in every conceivable attitude. The craze for collecting these pictures – a craze foreshadowing the popularity of first film stars and then pop stars – was not confined to the middle classes. Also many an aristocratic drawing room boasted a leather-bound, brass-locked album featuring the faces of the “Professional Beauty’s” of the season.[30]

In 1878 Lillie Langtry attracted a lot of attention during the Ascot races. Lady Augusta Fane: 'She was then at the height of her beauty and fame; wherever she went crowds of staring people followed her, even standing on chairs in the Park to look at the most advertised beauty in Europe. What really made Mrs. Langtry so wonderful was her charming personality and “naturalness.” She had no affections and no “make-up,” either of face or mind; she was just herself, so no one could help loving her, with her gay, light-hearted nature. Above all things she was no snob; indeed, had she possessed more worldly wisdom and less heart, she would not have quarrelled with her most illustrious friend for the sake of a handsome young peer of the realm! For a short time she was very happy as her youthful lover was devoted to her, and then he suddenly left her and eloped with the beautiful wife of an elderly man, but what appeared by making her life far more interesting, as it was the cause of her going on the stage and making a great name for herself. During her career she met and entertained most of the cleverest men of the day, travelled all over the world and was received with acclamation whenever she went. I saw Mrs. Langtry make her first appearance on the stage in She stoops to Conquer at the Haymarket Theatre. The house was packed with her friends and admirers applauded wildly. She looked lovely, but to me she seemed like a lost goddess who had strayed on to the stage by mistake.'[31]

However, there was another reason why Lillie Langtry attracted so much attention in 1878: the Prince of Wales was often seen in public with Lillie not very far away from him.

Royal mistress

[edit]

On 24 May, 1877, while his wife was staying in Athens with her brother, King George of Greece, the Prince of Edward visited the opera. Afterwards he took supper with the Arctic explorer, Sir Allen Young. With pre-arrangement he met for the first time the colourless sportsman Edward Langtry and his 23-years old wife Lillie. Just discovered one month earlier, Lillie had already taken London society by storm. She had attended all the gay parties and her photograph had appeared everywhere. Within a month of meeting the Prince of Wales, crowds started to collect whenever she, alone or in his company, she drove in London. It was presumed Lillie had become the mistress of Albert Edward, The Prince of Wales (later Edward VII - "Bertie" for family and friends). No scandal aroused. Alexandra, Princess of Wales accepted the situation and received Lillie Langtry for parties in Marlborough House, the London House of the Prince and Princess of Wales.[32]

The actor John Nettles (Bergerac, Midsomer Murders) wrote an introduction for a renewed publication of Lillie Langtry's memoirs: 'There was an elegant and simple logic which ruled Lillie Langtry's life. Her need was for fame and fortune and to achieve both she used her universally acknowledged beauty and vibrant sensuality, at first artlessly, but later with a courtesan's skill, to gain entry into the wondrously trivial and effete fin de siecle Society circles of the 1870s.' John Nettles, also born on Jersey, continued that Lillie Langtry enchanted the poet Oscar Wilde and the liberal Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone. 'Last, but not least, came the over-indulged and under-employed Bertie, Prince of Wales, heir to the Throne, more noted for his libido than his intellect, and very sensible indeed of Lillie's charms. In the stomach-churning prose of Pierre Sichel's "The Story of the Fabulous Mrs Langtry", this "dazzling Prince Charming, beautifully mannered, gracefully condescending, swept the young and beautiful island girl off her feet and away to his secret palace" - not quite to live happily ever after, but nearly enough to satisfy romantic expectations.'[33]

However, there are some doubts. Professor Jane Ridley has questioned the myth which Lillie Langtry created about herself and the role of King Edward VII inside that myth. In her biography Bertie, researched with (privileged) access to the Prince's paper in the British Royal Archives, she is quite critical about Lillie Langtry. In her view Lillie's narrative of herself as an innocent country girl to whom success just happened is disingenuous. Her assault on London society, though more spectacular than he could ever have dreamed, was carefully planned. Lillie Langtry admitted as much in an interview she gave to the New York Herald in 1882. Wearing a loose red robe and drying her waist-length hair before the fire, she told the reporter that the Le Breton family had a 'prescriptive right' to the deanery of Jersey, which they had held for generations. 'My pedigree was good and my person in Jersey society being assured, it was not surprising that I should be well-received.' She was introduced to London society, she claimed, by Lord Ranelagh, whose daughter had married her brother Clement. She was no adventuress. At the same time, Lillie Langtry denied she had ever set herself up as a beauty. 'I never thought I was one, and I don't think I am now. I am never in the least surprised when I hear people say they are very much disappointed about my beauty.' In Ridley's view, Lillie Langtry was lucky: she arrived in the season of the Professional Beauties. 'Do come, the P.B.'s will be there,' hostesses would scribble on their invitation cards. 'PB's were paraded as trophies at parties; like horseflesh their merits were compared and discussed. Artists in search of best-selling soft-porn pin-ups competed to paint them; their photograph were sold as postcards by the thousands; women stood on benches to spy them over the crowds in the park, and their dresses were instantly copied.'[34]

1878 was the year of triumph. Lillie and her husband Edward ("Ned") moved into a house at 17 Norfolk Street, off Park Lane. Cartes de visites of her photographs filled the window shops and the society papers were full of gossip about Lillie Langtry and her admirers within London society, including Crown Prince Rudolf of Austria. He had misread the signals. He had called often at Lillie's Norfolk Street House, presumably under the impression that Mrs Langtry was a royal poule de luxe, but he was not welcome.[35]

Jane Ridley expresses some doubts on the nature of the relationship with the Prince of Wales. The friendship between the "Professional Beauty" and the Prince of Wales has often been described as a domesticated love affair, but there is a hole - a silence - at the centre of the narrative. No letters from this time has survived.[36] Many of the stories seem to be exaggerated or wrong. Jane Ridley reconstructs a few exemples. Lillie is alleged to have consummated her relationship with Prince Edward when his wife, Alexandra ("Alix"), refused an invitation to accompany him to a royal house party at Crichel, Dorset, with Lord Arlington in January 1878. In fact, Alix was there. The princess even played a central role in the ball and festivities - which lasted a week. Lady Louise Manchester reported to Benjamin Disraeli (Lord Beaconsfield), the Prime Minister at the time, that Prince Edward was 'very snappish' throughout the whole visit; the Langtry's are not mentioned.[37]

According to Jane Ridley, Lillie Langtry published a false story about her presentation at court. In her memoirs she described how she was presented to Queen Victoria. Her husband had been presented a few weeks earlier, and Lillie's presentation validated her ambivalent social status. She was low down the list of ladies, but the Queen, who usually left her drawing rooms well before the end, stayed on purpose to see her, or so Lillie believed. Lillie describes in her memoirs: 'Queen Victoria looked straight in front her and, I thought, extended her hand in rather a perfuctory manner. There was not even the flicker of a smile on her face, and she looked grave and tired. My ordeal was not yet finished, for I had to curtsey to a long row of royalties, though, having met them all elsewhere previously, the smiled and shook hands as I passed. My curtseys began with the Prince and Princess of Wales, but they grew less and less profound and more slurred as I remembered I had one more vital moment to face before I was finally "out of the wood".... On the way home from the Palace, Lady Romeny expressed some surprise at the presence of Her Majesty till the very end of this particularly long drawing room but, that evening, while dancing in the Royal Quadrille at a ball at Marlborough House, I was enlightened as to the cause of the Queen's remaining. It seems that she had a great desire to see me, and had stayed on in order to satisfy herself as to my appearance. It was even added that she was annoyed because I was so late in passing. As to my appearance, I wondered what Her Majesty had thought of head-gear. I am afraid that waving ostrich plumes may have looked overdone, as the Prince of Wales that evening chaffed me good-humouredly on my conscientious observance of the Lord Chamberlain's order. At all events, I meant well.'[38] Jane Ridley states this anecdote seems to have been a make-believe on Lillie's part. 'Bertie was not present at Lillie's drawing room. He was in Paris. So was Alix. Lillie's presentation had been arranged in order to avoid embarrassment to the Princes of Wales.'[39]

In Jane Ridley's view, Lillie Langtry invented stories which implied she was, after the royal presentation and a meeting with Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli (Lord Beaconsfield) in the summer of 1878, recognized as royal mistress. 'As her biographer has observed, however, her career was one invention. She excelled at self-fashioning, carefully constructing an image of herself as royal mistress to project to the world.'[40]

There are more doubts. Biographers of Lillie Langtry have assumed the Prince of Wales gave orders to build a house for her in Bournemouth, so they could meet in anonymity.[41] Langtry Manor Hotel in Bournemouth claims the villa was built in order to serve as a "love nest" for Edward and Lillie. A quite important statement because Lillie's London house was not really available for meetings with lovers: her husband was often at home because he had little to do outside and mostly recovering from a hang-over or preparing one to come.[42] In reality, the Bournemouth house was built for Emily Langton Langton. The widowed Emily Langton Langton turned to temperance work with the British Women's Temperance Association, and in 1877 built the Red House at the junction of Knyveton Road and Derby Road, Bournemouth, including a large assembly room for her meetings.[43]

On suggestion of his publisher, the royal biographer Theo Aronson wrote a study of the three so-called official mistresses of King Edward VII: Lillie Langtry, Daisy Warwick and Alice Keppel. 'Fascinating stuff.'[44] After publishing The King in Love, Aronson was addressed with a lot of letters and telephone calls from people claiming to be the illegitimate descendants of King Edward VII. 'In spite of reading my book (or perhaps they haven't) in which I make clear that Edward's three-year-long liaison with Lillie Langtry was over by 1880, many of these correspondents claim descent from some childborn to King Edward VII and Lillie in the early 1900s, when she was well past childbearing age... Other have stories about secret "love nests" or underground passages which the King would use when entertaining Lillie Langtry (it is always her, never the other mistresses) despite the fact that by the time he became King, the affair had been over for a couple of decades.'[45] Jane Ridley draws a conclusion to this experience by Aronson. 'By keeping Lillie in secret houses, Bertie hoped to live a double life and shield Alix from embarrassment. The tales are revealing too about Lillie's ambivalent social status - in spite of her friendship with the prince, she was not considered a suitable house party guest.'[46]

In July 1879, Langtry began an affair with Lord Shrewsbury; in January 1880, Langtry and the earl were planning to run away together.[47] In the autumn of 1879, scandal-mongering journalist Adolphus Rosenberg wrote in Town Talk of rumours that her husband would divorce her and cite, among others, the Prince of Wales as co-respondent. Rosenberg also wrote about Patsy Cornwallis-West, whose husband sued him for libel. At this point, the Prince of Wales instructed his solicitor George Lewis to sue also. Rosenberg pleaded guilty to both charges and was sentenced to two years in prison.[48]

In 1880 a lot of things came together: the Shrewsbury scandal, rumours of divorce and a secret pregnancy – not by her husband. Many doors were shut heartlessly in her face. With the withdrawal of royal favour, creditors closed in. The Langtrys' finances were not equal to their lifestyle. In October 1880, Langtry sold many of her possessions to meet her debts, allowing Edward Langtry to avoid a declaration of bankruptcy.[49] Lillie went abroad to give life to a daughter. Afterwards, there was a necessity to rearrange her life. The Prince of Wales, staunch in friendship, procured an opening for her. He brought her in contact with the actor-manager Squire Bancroft, who controlled the Haymarket and the Prince of Wales’s theatres. Lillie Langtry used her fame and beauty to become a professional actrice. The Prince of Wales encouraged her by visiting the theatre while she was on stage and did everything in his power to help the inexperienced actress.[50]

Whatever it exacly was, Lillie's liaison with the Prince lasted from late 1877 to June 1880.[51][52]

Daughter

[edit]In April 1879, Langtry had had a short affair with Prince Louis of Battenberg, but also had a longer relationship with Arthur Clarence Jones (1854–1930). He was the brother of her sister-in-law and both were illegitimate children of Lord Ranelagh.[53] In June 1880, she became pregnant. Her husband was not the father; she led Prince Louis to believe that he was. When the prince told his parents, they had him assigned to the warship HMS Inconstant. The Prince of Wales gave her a sum of money, and Langtry went into her confinement in Paris, accompanied by Arthur Jones. On 8 March 1881, she gave birth to a daughter, whom she named Jeanne Marie.[53]

The discovery in 1978 of Langtry's passionate letters to Arthur Jones and their publication by Laura Beatty in 1999 support the idea that Jones was the father of Langtry's daughter.[54] Prince Louis' son, Earl Mountbatten of Burma, however, had always maintained that his father was the father of Jeanne Marie.[55]

Descendants

[edit]In 1902, Jeanne Marie Langtry married the Scottish politician Sir Ian Malcolm at St Margaret's, Westminster.[56] They had four children, three sons and a daughter. Jeanne Marie died in 1964. Her daughter Mary Malcolm was one of the first two female announcers on the BBC Television Service (now BBC One) from 1948 to 1956. She died on 13 October 2010, aged 92.[57] Jeanne Marie's second son, Victor Neill Malcolm, married English actress Ann Todd.[58] They divorced in the late 1930s. Victor Malcolm remarried in 1942, to an American, Mary Ellery Channing.[59]

Acting career and manager

[edit]

In 1881, Langtry was in need of money. Her close friend Oscar Wilde suggested she try the stage, and Langtry embarked upon a theatrical career.[60] She first auditioned for an amateur production in the Twickenham Town Hall on 19 November 1881. It was a comedy two-hander called A Fair Encounter, with Henrietta Labouchère taking the other role and coaching Langtry in her acting. Labouchère had been a professional actress before she met and married Liberal MP Henry Labouchère.

Following favourable reviews of this first attempt at the stage, and with further coaching, Langtry made her debut before the London public, playing Kate Hardcastle in She Stoops to Conquer at the West End's Haymarket Theatre in December 1881.[61] Critical opinion was mixed, but she was a success with the public. She next performed in Ours at the same theatre. Although her affair with the Prince of Wales was over, he supported her new venture by attending several of her performances and helping attract an audience.[62]

Early in 1882, Langtry quit the production at the Haymarket and started her own company,[63] touring the UK with various plays. She was still under the tutelage of Henrietta Labouchère.[62] American impresario Henry Abbey arranged a tour in the United States for Langtry. She arrived in October 1882 to be met by the press and Oscar Wilde, who was in New York on a lecture tour. Her first appearance was eagerly anticipated, but the theatre burnt down the night before the opening. The show moved to another venue and opened the following week. Eventually, her production company started a coast-to-coast tour of the US, ending in May 1883 with a "fat profit." Before leaving New York, she had an acrimonious break with Henrietta Labouchère over Langtry's relationship with Frederick Gebhard, a wealthy young American.[64] Her first tour of the US (accompanied by Gebhard) was an enormous success, which she repeated in subsequent years. While the critics generally condemned her interpretations of roles such as Pauline in The Lady of Lyons or Rosalind in As You Like It, the public loved her. After her return from New York in 1883, Langtry registered at the Conservatoire in Paris for six weeks' intensive training to improve her acting technique.[65]

In 1889, she took on the part of Lady Macbeth in Shakespeare's Macbeth. In 1903, she starred in the US in The Crossways, written by her in collaboration with J. Hartley Manners, husband of actress Laurette Taylor. She returned to the US for tours in 1906 and again in 1912, appearing in vaudeville. She last appeared on stage in America in 1917.[66] Later that year, she made her final appearance in the theatre in London.[62]

From 1900 to 1903, with financial support from Edgar Israel Cohen,[67] Langtry became the lessee and manager of London's Imperial Theatre. It opened on 21 April 1901, following an extensive refurbishment.[68] On the site of the theatre is now the Westminster Central Hall. In a film released in 1913 directed by Edwin S. Porter, Langtry starred opposite Sidney Mason in the role of Mrs Norton in His Neighbor's Wife in what would be her only film appearance.[69][70]

Thoroughbred racing

[edit]For nearly a decade, from 1882 to 1891, Langtry had a relationship with an American, Frederick Gebhard, described as a young clubman, sportsman, horse owner, and admirer of feminine beauty, both on and off the stage. Gebhard's wealth was inherited; his maternal grandfather Thomas E. Davis was one of the wealthiest New York real estate owners of the period. His paternal grandfather, Dutchman Frederick Gebhard, came to New York in 1800 and developed a mercantile business that expanded into banking and railroad stocks.[71] Gebhard's father died when he was 5 years old and his mother died when he was about 10. He and his sister, Isabelle, were raised by a guardian, paternal uncle William H Gebhard.[72]

With Gebhard, Langtry became involved in horse racing. In 1885, she and Gebhard brought a stable of American horses to race in England. On 13 August 1888, Langtry and Gebhard travelled in her private carriage[73] attached to an Erie Railroad express train bound for Chicago. Another railcar was transporting 17 of their horses when it derailed at Shohola, Pennsylvania, at 1:40 am. Rolling down an 80-foot (24 m) embankment, it burst into flames.[74] One person died in the fire, along with Gebhard's champion runner Eole and 14 racehorses belonging to him and Langtry. Two horses survived the wreck, including St Saviour, full brother to Eole. He was named for St Saviour's Church in Jersey, where Langtry's father had been rector and where she chose to be buried.[75][76] Despite speculation, Langtry and Gebhard never married. In 1895, he married Lulu Morris of Baltimore; they divorced in 1901.[77] In 1905 he married Marie Wilson; he died in 1910.[78]

In 1889, Langtry met "an eccentric young bachelor, with vast estates in Scotland, a large breeding stud, a racing stable, and more money than he knew what to do with": this was George Alexander Baird or Squire Abington,[79] as he came to be known. He inherited wealth from his grandfather, who with seven of his sons, had developed and prospered from coal and iron workings.[80] Baird's father had died when he was a young boy, leaving him a fortune in trust. In addition, he inherited the estates of two wealthy uncles who had died childless.[81]

Langtry and Baird met at a racecourse when he gave her a betting tip and the stake money to place on the horse. The horse won and, at a later luncheon party, Baird also offered her the gift of a horse named Milford. She at first demurred, but others at the table advised her to accept, as this horse was a very fine prospect. The horse won several races under Langtry's colours; he was registered to "Mr Jersey" (women were excluded from registering horses at this time). Langtry became involved in a relationship with Baird, from 1891 until his death in March 1893.[5][82][83][84]

When Baird died, Langtry purchased two of his horses, Lady Rosebery and Studley Royal, at the estate dispersal sale. She moved her training to Sam Pickering's stables at Kentford House[85] and took Regal Lodge as a residence in the village of Kentford, near Newmarket, Suffolk. The building is a short distance from Baird's original racehorse breeding establishment, which has since been renamed Meddler Stud.[86]

Langtry found mentors in Captain James Octavius Machell[87] and Joe Thompson, who provided guidance on all matters related to the turf. When her trainer Pickering failed to deliver results, she moved her expanded string of 20 horses to Fred Webb at Exning.[88] In 1899, James Machell sold his Newmarket stables to Colonel Harry Leslie Blundell McCalmont, a wealthy racehorse owner, who was Langtry's brother-in-law, having married Hugo de Bathe's sister Winifred in 1897. He was also related to Langtry's first husband, Edward, whose ship-owning grandfather George had married into the County Antrim Callwell family, being related in marriage to the McCalmonts.[89]

Told of a good horse for sale in Australia called Merman,[90] she purchased it and had it shipped to England; such shipments were risky and she had a previous bad experience with a horse arriving injured (Maluma). Merman was regarded as one of the best stayers; he eventually went on to win the Lewes Handicap, the Cesarewitch, Jockey Club Cup, Goodwood Stakes, Goodwood Cup, and Ascot Gold Cup (with Tod Sloan up).[91] Langtry later had a second Cesarewitch winner with Yentoi, and a third place with Raytoi. An imported horse from New Zealand called Uniform won the Lewes Handicap for her.[92]

Other trainers used by Langtry were Jack Robinson,[93] who trained at Foxhill in Wiltshire, and a very young Fred Darling,[94] whose first big success was Yentoi's 1908 Cesarewitch.[95]

Langtry owned a stud at Gazely, Newmarket. This venture was not a success. After a few years, she gave up attempts to breed blood-stock.[96] Langtry sold Regal Lodge and all her horse-racing interests in 1919 before she moved to Monaco. Regal Lodge had been her home for twenty-three years and received many celebrated guests, notably the Prince of Wales.[97]

In honour of her contributions to thoroughbred racing, since 2014 the Glorious Goodwood meeting has held the Group 2 Lillie Langtry Stakes.[98]

William Ewart Gladstone - Prime Minister

[edit]

During her stage career, Lillie Langtry became friendly with William Ewart Gladstone (1809–1898), who was the Prime Minister on four occasions during the reign of Queen Victoria. In her memoirs, Langtry says that she first met Gladstone when she was posing for her portrait at Millais' studio. Later he became a mentor to her.[99]

However, this was probably also a make-belief by Lillie Langtry herself. The actor John Nettles writes in the introduction of a renewed publication of Lillie's memoirs: 'No less a person than Liberal Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone, mixing prurience and morality in equal proportions, came to worship at her shrine (no doubt seeing the divine Langtry as an opportunity to extend his social work).'[100]

The biographers of William Ewart Gladstone think otherwise.They are also quite cynical about Lillie's motives.

Lillie Langtry in The Days I Knew: 'One of the most gratifying features of my debut was the concern in my new departure displayed by that gifted being, W.E.Gladstone. Although we had met casually at Millais's studio I had not known him further. But now he came often to see me and would drop in (he was Prime Minister at the time) to find me eating my dinner before going to the theatre. How wonderful it seemed that this great and universally sought-after man should give me and my work even a passing thougt. But he did more. His comprehensive mind and sweet nature grasped the difficult task that lay before me, the widely different orbit in which my life would henceforth move, and he knew how adrift I felt. And out of his vast knowledge of the public he realised how much he could help me - so the salmon advised the minnow. Never shall I forget the wisdom of Gladstone and the uplifting effects of his visits. Sometimes he read aloud his favounte passages from Shakeseare. Then, again, he would bring me books. He was truly religious, believing, he told me "with the simple faith of a child". And one could not be in his company without feeling that goodness emanating from him.... Among his many excellent admonitions I remember, and shall always remember, this sound piece of advice. He said. In "In your professional career, you will receive attacks, personal and critical, just and unjust. Bear them, never reply, and, above all, never rush into print to explam or defend yourself. And I never have.'[101]

However, it was not Gladstone who sought Lillie out; the approach came from Lillie. Abraham Hayward, an influential journalist, wrote Gladstone a letter, dated 8 January 1882: 'Mrs Langtry, who is an enthusiastic admirer of yours, told me this afternoon that she should be feel highly flattered if you would call on her, and I tell you this, although I fear you have other more pressing overtures just at present. Her address is 18 Albert Mansions, Victoria Street, and she is generally at home about six.'[102]

The published diaries of Gladstone show there were indeed contacts between Lillie Langtry and one of the most important British statesmen. However, the editor of Gladstone diaries doubts the friendship was, from Gladstone's point of view, important. Gladstone was a regular theatre-goer and moved enthusiastically among some theatre-sets. He frequently visited performances of drawing-room comedies and drama. Rumours were not surprising given Lillie's reputation and the gossip about Gladstone's nocturnal activities which circulated in London clubs. Gladstone was in the habit of wanting to "rescue" prostitutes by trying to convince them it was best not to live in sin and to find a decent job. Gladstone noted on 3 April 1882 in his diary: 'I hardly know what estimate to form of her. Her manners are very pleasing, & she has a working spirit in her'. On 16 February 1885 he wrote: 'Saw Mrs Langtry: probably for the last time.'[103] Gladstone's private secretary was worried about the contacts between Lillie Langtry and Gladstone: he was afraid she tried to make social capital out of their contacts. 'Last week Mr. G. received an invitation to a Sunday "at home" from Mrs Langtry. He did not avail himself of it, but he went and called at her house. He did not even see her, but all kinds of rumours are already abroad about his intimacy with the "professional beauty". These rumours would have had much greater currency and better foundation, had he gone to the evening party, out of which I think we managed to frighten him and the card for which I first thought of hiding and saying nothing about. Certainly Rosebery spoke not a day too early about the night walks, which are now openly talked of in Society.'[104] Things even became worse. Gladstone presented Lillie Langry a copy of his favourite book, Sister Dora- a biography of a high-born woman who worked as a nurse among the poor. Hamilton:'She is evidently trying to make social capital out the acquaintance which scraped with him. Most disagreeable things with all kinds of exaggeration are being said. I took the occasion of putting a word and cautioning him against the wiles of the woman, whose reputation is in such bad odour that, despite all the endeavours of H.R.H., nobody will receive in their houses.'.[105] It seems Lillie Langtry had become by April 1882 a social outcast, with two important men who tried to help her: the Prince of Wales and the Prime Minister. Hamilton tried to protect his boss, but had a shrewd woman against him. 'She had evidently been told to resort to the double-enveloppe system which secures respect from our rude hand; and she is now making pretty constant use of this privilege and boasting in proportion.'.[106] Hamilton could do nothing: the letters became more frequently, but he couldn't read them.[107] However, the published diaries of Gladstone himself shows Hamilton had little to fear: there were little personal contacts with Lillie Langtry. Gladstone wrote her exactly one letter in the short period after Lillie tried to (re)make contact with him while Gladstone didn't know well how to deal with the situation.[108]

In 1925, Captain Peter Emmanuel Wright published a book called Portraits and Criticisms. In it, he claimed that Gladstone had numerous extramarital affairs, including one with Langtry. Gladstone's son Herbert Gladstone wrote a letter calling Wright a liar, a coward and a fool; Wright sued him. During the trial, a telegram, sent by Langtry from Monte Carlo, was read out in court saying, "I strongly repudiate the slanderous accusations of Peter Wright." The jury found against Wright, saying that the "gist of the defendant's letter of 27 July was true" and that the evidence vindicated the high moral standards of the late Gladstone.[109][110]

American citizenship and divorce

[edit]In 1888, Langtry became a property owner in the United States when she and Frederick Gebhard purchased adjoining ranches in Lake County, California. She established a winery with an area of 4,200 acres (17 km2) in Guenoc Valley, producing red wine.[111] She sold it in 1906. Bearing the Langtry Farms name, the winery and vineyard are still in operation in Middletown, California.[112]

During her travels in the United States, Langtry became an American citizen and on 13 May 1897, divorced her husband Edward in Lakeport, California. Her ownership of land in America was introduced in evidence at her divorce to help demonstrate to the judge that she was a citizen of the country.[113] In June of that year Edward Langtry issued a statement giving his side of the story, which was published in the New York Journal.[114]

Edward died a few months later in Chester Asylum, after being found by police in a demented condition at Crewe railway station. His death was probably the result of a brain haemorrhage after a fall during a steamer crossing from Belfast to Liverpool. He was buried in Overleigh Cemetery; a verdict of accidental death was returned at the inquest.[115][116][117] A letter of condolence later written by Langtry to another widow reads in part, "I too have lost a husband, but alas! it was no great loss."[118]

Langtry continued to have involvement with her husband's Irish properties after his death. These were compulsorily purchased from her in 1928 under the Northern Ireland Land Act, 1925. This was passed after the Partition of Ireland, with the purpose of transferring certain lands from owners to tenants.[119][120]

Hugo Gerald de Bathe

[edit]After the divorce from her husband, Langtry was linked in the popular press to Prince Paul Esterhazy, an Austro-Hungarian diplomat. They shared time together and both had an interest in horse-racing.[121] However, in 1899, she married 28-year-old Hugo Gerald de Bathe (1871–1940), son of Sir Henry de Bathe, 4th Baronet, and Charlotte Clare. Hugo's parents had initially not married, because of objections from the de Bathe family. They lived together and seven of their children were born out of wedlock. They married after the death of Sir Henry's father in 1870. Hugo was their first son to be born in wedlock – making him heir to the baronetcy.[122]

The wedding between Langtry and de Bathe took place in St Saviour's Church, Jersey, on 27 July 1899,[123] with her daughter Jeanne Marie Langtry being the only other person present, apart from the officials. This was the same day that Langtry's horse Merman won the Goodwood Cup. In December 1899, de Bathe volunteered to join the British forces in the Boer War. He was assigned to the Robert's Horse Mounted brigade as a lieutenant. In 1907, Hugo's father died; he became the 5th Baronet, and Langtry became Lady de Bathe.[124]

When Hugo de Bathe became the 5th Baronet, he inherited properties in Sussex, Devon and Ireland; those in Sussex were in the hamlet of West Stoke near Chichester. These were Woodend, with 17 bedrooms and set in 71 acres; Hollandsfield, with 10 bedrooms and set in 52 acres; and Balsom's Farm of 206 acres. Woodend was retained as the de Bathe residence whilst the smaller Hollandsfield was let.[125] Today the buildings retain their period appearance. Modifications and additions have been made, and the complex is now multi-occupancy. One of the houses on the site is named Langtry and another Hardy. The de Bathe properties were all sold in 1919, the same year Lady de Bathe sold Regal Lodge.[126]

Final days

[edit]During her final years, Langtry, as Lady de Bathe, resided in Monaco whilst her husband, Sir Hugo de Bathe, lived in Vence, Alpes Maritimes.[127] The two saw one another at social gatherings or in brief private encounters. During World War I, Hugo de Bathe was an ambulance driver for the French Red Cross.[128][129]

Langtry's closest companion during her time in Monaco was her friend Mathilde Marie Peat. Peat was at Langtry's side during the final days of her life as she was dying of pneumonia in Monte Carlo. Langtry left Peat £10,000, the Monaco property known as Villa le Lys, clothes, and her motor car.[130]

Langtry died in Monaco at dawn on 12 February 1929. She had asked to be buried in her parents' tomb at St Saviour's Church in Jersey. Blizzards delayed the journey, but her body was taken to St Malo and across to Jersey on 22 February aboard the steamer Saint Brieuc. Her coffin lay in St Saviour's overnight surrounded by flowers, and she was buried on the afternoon of 23 February.[131]

Bequests

[edit]In her will, Langtry left £2,000 to a young man of whom she had become fond in later life, named Charles Louis D'Albani; the son of a Newmarket solicitor, he was born in about 1891. She also left £1,000 to A. T. Bulkeley Gavin of 5 Berkeley Square, London, a physician and surgeon who treated wealthy patients. In 1911 he had been engaged to author Katherine Cecil Thurston, who died before they could marry; she had already changed her will in favour of Bulkeley Gavin.[132]

Cultural influence and portrayals

[edit]Langtry used her high public profile to endorse commercial products such as cosmetics and soap—an early example of celebrity endorsement.[1] She used her famous ivory complexion to generate income, being the first woman to endorse a commercial product when she began advertising Pears Soap in 1882.[133] The aesthetic movement in England became directly involved in advertising, and Pears (under advertising pioneer Thomas J. Barratt) recruited Langtry—who had been painted by aesthete artists—to promote their products, which included putting her "signature" on the advertisements.[134][135]

In the 1944 Universal film The Scarlet Claw, Lillian Gentry, the first murder victim, wife of Lord William Penrose and former actress, is an oblique reference to Langtry.[136]

Langtry has been portrayed in two films. Lilian Bond played her in The Westerner (1940), and Ava Gardner in The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean (1972). Bean was played by Walter Brennan in the former, and by Paul Newman in the latter film.[136]

In 1978, Langtry's story was dramatised by London Weekend Television and produced as Lillie, starring Francesca Annis in the title role (Annis received the British Academy Television Award for Best Actress). Annis previously played Langtry in two episodes of ATV's Edward the Seventh. Jenny Seagrove played her in the 1991 television film Incident at Victoria Falls.[136]

Langtry is a featured character in the fictional The Flashman Papers novels of George MacDonald Fraser, in which she is noted as a former lover of arch-cad Harry Flashman, who, nonetheless, describes her as one of his few true loves.[137]

Langtry is suggested as an inspiration for Irene Adler, a character in the Sherlock Holmes fiction of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.[138] In "A Scandal in Bohemia", Adler bests Holmes, perhaps the only woman to do so.

Langtry is used as a touchstone for old-fashioned manners in Preston Sturges's comedy The Lady Eve (1941), in a scene where a corpulent woman drops a handkerchief on the floor and the hero ignores it. Jean (Barbara Stanwyck) begins to describe, comment, and anticipate the events that we see reflected in her hand mirror: "The dropped kerchief! That hasn't been used since Lillie Langtry ... you'll have to pick it up yourself, madam ... it's a shame, but he doesn't care for the flesh, he'll never see it."[139]

Lillie Langtry is the inspiration for The Who's 1967 hit single "Pictures of Lily", as mentioned in Pete Townshend's 2012 memoir Who I Am.[140] Dixie Carter portrays Langtry as a "songbird" and Brady Hawkes' love interest in Kenny Rogers' 1994 Gambler V: Playing for Keeps, the last of the Gambler series for CBS that started in 1980. Langtry is depicted as a singer, not an actress, and Dixie Carter's costuming appears closer to Mae West than anything Langtry ever wore.[141]

In The Simpsons 1994 episode "Burns' Heir", the auditions are held in the Lillie Langtry Theater on Burns' estate.[142]

Langtry is a featured character in the play Sherlock Holmes and the Case of the Jersey Lily by Katie Forgette. In this work, she is blackmailed over her past relationship with the Prince of Wales, with intimate letters as proof. She and Oscar Wilde employ Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson to investigate the matter.[143]

Places connected with Lillie Langtry

[edit]Residences and historical namesakes

[edit]When first married (1874), Edward and Lillie Langtry had a property called Cliffe Lodge in Southampton, Hampshire.[144] In 1876 they rented an apartment in Eaton Place, Belgravia, London. From early 1878 they lived at 17 Norfolk Street (now 19 Dunraven Street) in Mayfair, London. Langtry lived at 21 Pont Street, London, from 1890 to 1897, and had with her eight servants at the 1891 census.[5] Although from 1895 the building was operated as the Cadogan Hotel, she would stay in her former bedroom there. A blue plaque (which erroneously states that she was born in 1852) on the hotel commemorates this, and the hotel's restaurant is named 'Langtry's' in her honour.[145]

A short walk from Pont Street was a house at number 2 Cadogan Place where she lived in 1899.[146] From 1886 to 1894, she owned a house in Manhattan at 362 West 23rd Street, a gift from Frederick Gebhard.[147]

Langtry's London address from 1916 until at least 1920 was Cornwall Lodge, Allsop Place, Regent's Park. She gave this address when sailing on the liner St Paul across the Atlantic in August 1916,[148] and the 1920 London electoral register has de Bathe, Emilie Charlotte (Lady), listed at the same address.[149] A letter sold at auction in 2014 from Langtry to Dr. Harvey dated 1918 is also headed with this address.[150] Langtry was a cousin of local politician Philip Le Breton, pioneer for the preservation of Hampstead Heath, whose wife was Anna Letitia Aikin.[151][152]

There are two bars in New York City devoted to the memory of Lillie Langtry, operating under the title Lillie's Victorian Establishment.[153] Judge Roy Bean named the saloon, in Pecos, Texas, The Jersey Lily, which also served as the judge's courthouse, for her, in Langtry, Texas (named after the unrelated engineer George Langtry).[154]

Spurious associations

[edit]Bournemouth

[edit]In 1938 the new owners of the Red House at 26 Derby Road, Bournemouth, which had been built in 1877 by the widowed women's rights campaigner and temperance activist Emily Langton Langton, converted the large house into a hotel, the Manor Heath Hotel, and advertised it as having been built for Lillie Langtry by the Prince of Wales, believing that the inscription 'E.L.L. 1877' in one of the rooms related to Lillie Langtry. A plaque was later placed on the hotel by Bournemouth Council repeating the assertion, and in the late 1970s the hotel was renamed Langtry Manor. However, despite the hotel's claims and local legend, no actual association between Langtry and the house ever existed and the Prince never visited it.[155]

South Hampstead

[edit]On 2 April 1965[156][157] the Evening Standard reported an interview with Electra Yaras (born c. 1922),[158] leaseholder and resident of Leighton House, 103 Alexandra Road, South Hampstead,[157] who claimed in the interview that Langtry had lived in the house and regularly entertained the Prince of Wales there.[156] Yaras claimed that she herself had been visited in the house several times by Langtry's ghost.[158][156]

On 11 April 1971[157] The Hampstead News said that the house had been built for Langtry by Lord Leighton.[158] These claims by Yaras and later by The Hampstead News were made in order to suggest an historical importance for the house and support its preservation from the demolition which had been originally ordered in 1965 and revived in 1971.[158][156][157] The claims were supported in 1971 by actress Adrienne Corri, who lived nearby[157] and signed a petition,[159] and were publicised in The Times on 8 October 1971[157][158] and The Daily Telegraph on 9 October 1971.[157][159] They were given further publicity by Anita Leslie in 1973 in a book on the Marlborough House set.[160]

The house was nevertheless demolished in 1971 to make way for the Alexandra Road Estate.[159][157][158]

In 2021, published research revealed that the house had been built in the 1860s by Samuel Litchfield and was likely named after his wife's birthplace of Leighton Buzzard.[158][157] Lengthy research into local records by Dick Weindling and Marianne Colloms revealed no connection whatever with Langtry.[159][158]

The persistence of the myth, propounded in a time when stories about the royal family were easy to publicise and received no critical or substantiating research,[158] resulted in Langtry's name still being in use in some place names and locales in the South Hampstead area.[157][159][158] These include Langtry Road off Kilburn Priory; Langtry Walk in the Alexandra Road Estate; and the Lillie Langtry pub at 121 Abbey Road (defunct since late 2022),[161] built in 1969 to replace The Princess of Wales hotel, and briefly called The Cricketers from 2007 to 2011.[162] The mythologizing also includes The Lillie Langtry pub at 19 Lillie Road in Fulham – the road actually took its name from local landowner John Scott Lillie.[163]

Steam yacht White Ladye

[edit]

Langtry owned a luxury steam auxiliary yacht called White Ladye from 1891 to 1897. The yacht was built in 1891 for Lord Asburton by Ramage & Ferguson of Leith, Scotland, from a design by W. C. Storey. She had three masts, was 204 feet in length and 27 feet in breadth and was powered by a 142 hp steam engine. She had originally been named Ladye Mabel.[164]

In 1893, Ogden Goelet leased the vessel from Langtry and used it until his death in 1897.[165] Langtry put the White Ladye up for auction in November 1897 at the Mart, Tokenhouse Yard, London. It was sold to Scottish entrepreneur John Lawson Johnston, the creator of Bovril.[166] He owned it until his death on board in 1900.[167] From 1902 to 1903, the yacht was recorded in the Lloyd's Yacht Register as being owned by shipbuilder William Cresswell Gray, Tunstall Manor, West Hartlepool, and remained so until 1915. Following this the Lloyd's Register records that she became adapted as French trawler La Champagne based in Fécamp, northwest France; she was broken up in 1935.[168]

Bibliography

[edit]- Langtry, Lillie, The Days I Knew(registration required), 1925 autobiography).

- Langtry, Emilie Charlotte. The life of Mrs. Langtry, the Jersey Lily, and queen of the stage, 1882. Pinder & Howes Leeds[169]

- Langtry, Lillie. All at Sea (novel) 1909.[170]

-

All at Sea, Langtry's only novel

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Constructs such as ibid., loc. cit. and idem are discouraged by Wikipedia's style guide for footnotes, as they are easily broken. Please improve this article by replacing them with named references (quick guide), or an abbreviated title. (December 2024) |

- ^ a b c "When Celebrity Endorsers Go Bad". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

British actress Lillie Langtry became the world's first celebrity endorser when her likeness appeared on packages of Pears Soap.

- ^ Richards, Jef I. (2022). A History of Advertising: The First 300,000 Years. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 286.

- ^ "Lillie Langtry British actress". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ "Lillie Langtry". jaynesjersey.com. Archived from the original on 15 February 2015. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- ^ a b c Camp, Anthony. Royal Mistresses and Bastards: Fact and Fiction: 1714–1936 (2007), p. 366.

- ^ "Home JerripediaBMD". search.jerripediabmd.net. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ^ However, Lillie's pedigree in Burke's Landed Gentry (vol. 3, 1972, pages 526–7) begins in the fifteenth century and suggests a descent from 'Sir Reginald Le Breton, one of the four kts. concerned in the death of Thomas a Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury'.

- ^ Langtry, Lillie (1989). The Days I Knew – An Autobiography. St. John: Redberry Press. p. Chapter 1 – Call Me Lillie.

- ^ Camp, Anthony. Royal Mistresses and Bastards: Fact and Fiction 1714–1936 (London, 2007). p. 365. ISBN 9780950330822

- ^ "Marriage Register of St Saviour's Church – entry for Edward Langtry, 26 and Emilie Charlotte de Breton, 20". Jersey Heritage. Retrieved 24 July 2019.

- ^ Dudley, Ernest (1958). The Gilded Lily. London: Odhams Press Limited. pp. 34–35.

- ^ "The Yacht Red Gauntlet". Illustrated Australian News. 22 March 1882. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ Aronson, Theo (1989). The King in Love. London: Corgi Books. p. 74.

- ^ "Interview with the Jersey Lillie". Daily Telegraph. No. 3507. 3 October 1882. p. 4. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ^ "Looking for Lillie Langtry". kilburnwesthampstead.blogspot.com.

- ^ Beatty, Laura (1999). "Chapter III:London". Lillie Langtry: Manners, Masks and Morals. Chatto & Windus. ISBN 1-8561-9513-9.

- ^ Langtry, Lillie (2000). The Days I Knew. Panoply Publications. p. Chapter 2.

- ^ "Frank Miles Drawing". lillielangtry.com. Retrieved 30 May 2008.

- ^ a b Crosby, Edward Harold (23 January 1916). "Under the Spotlight". Boston Sunday Post. p. 29.

- ^ Potter, Rupert (September 1879). "A Jersey Pair". V&A Search and Collection. V&A. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- ^ Margot Asquith, The Autobiography of Margot Asquith (Thornton Butterworth, London, 1920) 58

- ^ Margot Asquith, Countess of Oxford,More Memories(Cassell, London 1933) 31-32

- ^ Frances, Countess of Warwick, Life's Ebb & Flow (Hutchinson & Co, London, 1929) 46-47. Lady Warwick was also a very good friend of King Edward VII and supposed to be more than that.

- ^ Theo Aronson, The King in Love. The King in Love (John Murray, London, 1988) 31.

- ^ Aronson, King in Love', 32. '

- ^ Aronson, King in Love, 23.

- ^ Aronson, King in Love, 23-24.

- ^ Aronson, King in Love, 24.

- ^ Aronson, King in Love, 25

- ^ Aronson, King in Love, 34.

- ^ Lady Augusta Fane, Chit-Chat (Thornton Butterworth, London, 1926) 70-71.

- ^ Philip Magnus, King Edward the Seventh (London 1964) 153-154; Gordon Brook-Shepherd, Uncle of Europe. The Social and Diplomatic Life of Edward VII (London 1975) 55-56

- ^ John Nettles in: Lillie Langtry, The Days I knew - An Autobiography(Redberry Press, 1989) vii.

- ^ Jane Ridley, Bertie. A Life of Edward VII (London 2012) 202-204.

- ^ Ridley, Bertie, 206-207.

- ^ Ridley, Bertie, 207. Theo Aronson assumes that Lillie Langtry has probably destroyed compromising letters just like she refused many offers from publishers to write revealing memoirs. Her published memories in The Days I Knew were innocent. There is no mention in The Days I Knewabout her extramarital daughter; most of her lovers, including Prince Louis of Battenberg, are not even mentioned. Aronson, King in Love, 260-268. Philip Magnus describes in his biography King Edward the Seventh (page 461) that the king had ordered by his will that all his private and personal correspondence, including those with Queen Alexandra and Queen Victoria, should be destroyed. All papers after his death were in 'dire confusion' and it was clear a vast number of papers were burned.

- ^ Ridley, Bertie, 207.

- ^ Lillie Langty, The Days I Knew (Redberry Press, 1989) 65-66.

- ^ Ridley, Bertie, 207.

- ^ Ridley, Bertie, 211; referring to Beatty, Lillie Langtry, 1-9.

- ^ Aronson,King in Love, 48; Beatty, Lillie Langtry, 88–89.

- ^ Beatty, Lillie Langtry,87

- ^ https://anthonyjcamp.com/pages/anthony-j-camp-additions

- ^ Theo Aronson, Royal Subjects. A Biographer's Encounters (Pan Books, 2001),108.

- ^ Theo Aronson, Royal Subjects. A Biographer's Encounters (Pan Books, 2001, 122-123.

- ^ Ridley, Bertie, 212

- ^ Beatty, Laura (1999). "XIX: Storm Clouds". Lily Langtry: Manners, Masks and Morals. London: Chatto & Windus. pp. 164–165. ISBN 1-8561-9513-9.

- ^ Juxon, John (1983). Lewis & Lewis. London: Collins. p. 179.

- ^ "Changing fortunes". jaynesjersey.com. Archived from the original on 15 February 2015. Retrieved 30 May 2008.

- ^ Magnus, King Edward the Seventh, 172-173; Brook-Shepherd, Uncle of Europe, 56-59

- ^ Beatty, Laura (1999). "XX: The Storm Breaks". Lily Langtry: Manners, Masks and Morals. London: Chatto & Windus. p. 173. ISBN 1-8561-9513-9.

- ^ Camp, Anthony. Royal Mistresses and Bastards: Fact and Fiction: 1714–1936 (2007), pp. 364–67.

- ^ a b Camp, Anthony. Royal Mistresses and Bastards: Fact and Fiction: 1714–1936 (2007), pp. 364–67

- ^ Beatty, op. cit.

- ^ Daily Telegraph, 27 September 1978; Evening News, 23 October 1978.

- ^ "MISS LANGTRY'S WEDDING". Kalgoorlie Miner. Vol. 7, no. 18437. Western Australia. 5 August 1902. p. 6. Retrieved 8 April 2016 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Purser, Philip (14 October 2010). "Mary Malcolm obituary". The Guardian. London.

- ^ "Untitled". The Australasian. Vol. CXLII, no. 4. Victoria, Australia. 13 February 1937. p. 13. Retrieved 8 April 2016 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Miss Channing to wed V. N. Malcolm in Washington". New York Sun. 5 February 1942.

- ^ Langtry, Lillie (2000). The Days I Knew. Panoply Publications. p. 123.

- ^ New International Encyclopedia

- ^ a b c Dudley, Ernest (1958). The Gilded Lily. London: Odhams Press Limited. p. Chapters 6–8.

- ^ Dudley, Ernest (1958). The Gilded Lily. London: Oldhams Press. p. 73.

- ^ Beatty, Laura (1999). Lillie Langtry – Manners, Masks and Morals. London: Vintage. p. Chapter XXVII Down the Primrose Path.

- ^ Beatty, Laura (1999). "XXVIII ("Venus in Harness")". Lillie Langtry – Manners, Masks and Morals. London: Vintage.

- ^ "Los Angeles Herald 23 September 1916 — California Digital Newspaper Collection". cdnc.ucr.edu.

- ^ "FORTUNE OF FIVE Millions". The Evening News. No. 3752. Queensland, Australia. 14 October 1933. p. 3. Retrieved 28 March 2016 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Mrs Langtry sold the theatre to Wesleyan Methodists. They later sold [the interior] to the company owning the Royal Albert Music Hall, Canning Town. They reconstructed the theatre stone by stone as the Music Hall of Dockland".

Templeman Library, University of Kent at Canterbury - ^ Fryer, Paul (2012). Women in the Arts in the Belle Epoque: Essays on Influential Artists, Writers and Performers. McFarland. p. 57.

- ^ Wilson, Scott (2016). Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons, 3d ed. McFarland. p. 425.

- ^ Barrett, Walter (1863). The old merchants of New York City. New York: Carleton. p. 132.

- ^ "Disposing of Two Million" (PDF). The New York Times. 28 June 1878. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

- ^ "Mrs Langtry's Railway Traveling Saloon". The Decorator and Furnisher. December 1884.

- ^ "Wreck on the Erie Road". The Sun. 14 August 1888. p. 5. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ^ The New York Times, 14 August 1888, p. 33

- ^ The New York Times, 15 August 1888, p. 20

- ^ "Mr Frederick Gebhard to Pay His Divorced Wife a Fortune. ... ". The San Francisco Call. 30 October 1901. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- ^ "Fred Gebhard Near Death" (PDF). New York Times. 22 April 1910. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ^ "Baird, George Alexander (1861– 93)". Copyright © 2003 All rights reserved worldwide The National Horseracing Museum. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- ^ Bulloch, John Malcolm (1934). The last Baird Laird of Auchmedden and Strichen. The case of Mr. Abington [i.e. George Alexander Baird.]. Aberdeen: Privately printed. p. 2.

- ^ Bulloch, John Malcolm (1934). The Last Baird of Auchmedden and Strichen. Aberdeen: Privately Printed. p. 2. ISBN 9780806305431.

- ^ "Lillie Langtry and George Baird of Stichill". Thanks to Stichill Millennium Project. Bairdnet. Archived from the original on 10 April 2013. Retrieved 22 March 2012.

- ^ Dudley, Ernest (1958). The Gilded Lily. London: Oldhams Press. pp. 128–34.

- ^ "Baird's of Stichill". thank to Stitchill Millennium Project. Bairnet. Archived from the original on 10 April 2013. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ^ "Pickering, Samuel George (1865– 1927)". The National Horseracing Museum. 2003. Archived from the original on 11 November 2013. Retrieved 27 March 2013.

- ^ Dudley, Ernest (1958). The Gilded Lily. London: Oldhams Press. pp. Chapter 14 and Postscript.

- ^ "Machell, James Octavius (Captain) (1837–1902)". Copyright © 2003 All rights reserved worldwide The National Horseracing Museum. Archived from the original on 14 December 2007. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- ^ "Webb, Frederic E (1853–1917)". Copyright © 2003 All rights reserved worldwide The National Horseracing Museum. Archived from the original on 17 May 2005. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- ^ Bigger, Francis Joseph (1916). The Magees of Belfast and Dublin, Printers. W&G Baird. p. 26. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ^ Allison, William (c. 1917). My Kingdom for a Horse. New York: E.P. Dutton & Company. p. 346.

- ^ The New York Times, 15 June 1900, p. 16

- ^ Sussex Express Archived 6 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine (Consultado el 5 de noviembre de 2016)

- ^ "Robinson, William Thomas (1868–1918)". The National Horseracing Museum. Archived from the original on 27 February 2004. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- ^ "Darling, Frederick (1884–1953)". The National Horseracing Museum. Archived from the original on 18 March 2004. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- ^ The New York Times, October 15, 1908. Retrieved November 2016

- ^ Langtry, Lillie (2000). The Days I Knew. Panoply Publications. p. Chapter 18 ("The Races").

- ^ "Kentford Village History". A Forest Heath District Council (Suffolk) Project. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 24 March 2012.

- ^ "European Pattern Committee announces changes to the 2018 European Programme of Black Type Races". British Horseracing Authority. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- ^ Langtry, Lillie (2000). The Days I Knew. Panoply Publications. p. Chapter 10 ("Young and Optimistic").

- ^ John Nettles in: Langtry, The Days I Knew (1989) viii.

- ^ Langtry, The Days I knew, 102-103

- ^ Quoted by Aronson, King in Love, 95-96. Aronson himself refers to the Gladstone Papers, in the British Manuscript Library, London, 44207/193, 8/1/1882

- ^ H.C.G. Matthew, Gladstone 1809-1898 (Oxford 1997) 527. In the diaries themselves Gladstone only recorded that he saw Mrs Langtry (26 January 1882), saw a play in which she acted (4 February 1882), wrote her a letter (25 February 1882) and said goodbye to her in probably their last meeting (16 February 1885). Afterwards he only saw Lillie Langtry while she acting on stage Cleopatra (6 December 1890). The Gladstone Diaries with Cabinet minutes and pre-ministerial correspondence. Compiled by H.C.G. Matthews. Volume X (January 1881 - June 1883; Oxford 1990): 201, 207, 215, 230; volume XI (July 1883 - December 1886; Oxford 1990): 296; Volume XII (1887-1891; Oxford 1994): 348.

- ^ The Diary of Sir Edward Walter Hamilton 1880-1885. Edited by Dudley W.R. Bahlman (Oxford 1972), volume I (1880-1882), 232 (7 March 1882).

- ^ The Diary of Sir Edward Walter Hamilton, I, 245 (1 April 1882).

- ^ The Diary of Sir Edward Walter Hamilton, I, 257 (20 April 1882).

- ^ The Diary of Sir Edward Walter Hamilton, I, 265 (5 May 1882).

- ^ In his diaries Gladstone made notes of all people he met during the day, the letters he wrote and the books he read. The general index of The Gladstone Diaries (volume XIV, 1994) shows exactly 6 entries during his whole (fully recorded) life relating to Lillie Langtry. Biographers shared Hamilton's anxiety before the diaries were published: Philip Magnus, Gladstone. A Biography (London 1954) 305-306; Joyce Marlow, Mr and Mrs Gladstone (London 1977) 215-218. Em. professor Richard Shannon, who wrote the standard biography of Gladstone after the publication of the complete diaries: 'Being introduced on 3 April to the "Jersey Lily", the actress Mrs Langtry, was for Gladstone some of a puzzle. She seemed not to fit quite into any of the categories of demi-mondaines with which he was familiar. "I hardly know what estimate to form her. Her manners are very pleasing, and she had a working spirit".' Richard Shannon, Gladstone: Heroic Minister, 1865-1898 (Allen Lane/The Penquin Press, London, 1999) 294. Prof. Travis L. Crosby just ignored Lillie Langtry in his psychobiographical study: Travis L. Crosby, The Two Mr. Gladstones. A Study in Psychology and History (Yale University Press, New Haven & London, 1997). Richard Shannon did the same in his more revisionist, themed study on Gladstone (after finishing his biography): Richard Shannon, Gladstone - God and Politics (Continuum, London, 2007).

- ^ "THE GLADSTONE CASE". The Advertiser. Adelaide. 3 February 1927. p. 13. Retrieved 18 June 2015 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "The Gladston Case; Verdict Against Capt. Wright". The Times. No. 14. 4 February 1927.

- ^ Stoneberg, David (7 September 2020). "Massive resort development planned in southern Lake County". Napa Valley Register. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ "The Life of Lillie Langtry" (PDF). Langtry Farms. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 November 2014. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- ^ "Mrs. Langtry's Divorce". The Telegraph. No. 7700. Brisbane. 1 July 1897. p. 2. Retrieved 6 April 2016 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "THE JERSEY LILY". The Sunday Times. No. 604. Sydney. 25 July 1897. p. 9. Retrieved 6 April 2016 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Mr Edward Langtry". Adelaide Observer. Vol. LIV, no. 2, 925. 23 October 1897. p. 6. Retrieved 6 April 2016 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Beatty, op. cit., p. 302.

- ^ New York Times, 17 October 1897.

- ^ Letter in the Curtis Theatre Collection, University of Pittsburgh.

- ^ "LAND PURCHASE COMMISSION, NORTHERN IRELAND LAND ACT, 1925" (PDF). thegazette.co.uk/Belfast. The Gazette. 20 July 1928. p. 735. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- ^ "Estate of Lady Lily de Bathe (Widow), Representative of Edward Langtry, Deceased". www.thegazette.co.uk/Belfast. The Gazette. 14 September 1928. p. 1007. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- ^ "Mrs Lantry to Marry" (PDF). The New York Times. 25 September 1897. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- ^ "Legitimacy Declaration". The Times. No. Page 5 Column 5. 22 February 1928.

- ^ "The Life of Lillie Langtry" (PDF). Langry Farms (California). 2016. p. 20. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 November 2014. Retrieved 26 May 2016.

On July 27, 1899 at St Saviour's church, she quietly married Hugo de Bathe, 28 years old. She was 46. Her horse, Merman, won the Goodwood Cup for her on that same day.

- ^ Dudley, Ernest (1958). The Gilded Lily. London: Odham Press. pp. 160–63.

- ^ Beckett, J.V. (1994). The Rise and Fall of the Grenvilles: Dukes of Buckingham and Chandos, 1710 to 1921. Manchester University Press. p. 104. ISBN 9780719037573. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- ^ "Regal Lodge sold privately". Bury Free Press. 5 July 1919.

- ^ "Lily Langtry's Husband". The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser. 26 June 1931. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ^ The National Archives of the UK; Kew, Surrey, England. WWI Service Medal and Award Rolls; Class: WO 329; Piece Number: 2324

- ^ Army Medal Office. WWI Medal Index Cards. In the care of The Western Front Association website

- ^ Beatty, Laura (1999). Lillie Langtry – Manners, Masks and Morals. London: Vintage. p. Chapter XXXIV ("Final Act").

- ^ Dudley, Ernest (1958). The Gilded Lily. London: Oldhams Press. pp. 219–20.

- ^ Copeland, Caroline (2007). The Sensational Katherine Cecil Thurston: An Investigation into the Life and Publishing History of a 'New Woman' Author (PDF). ©Caroline Copeland 2007. pp. various. Retrieved 11 April 2016.