Furthur (bus)

| Furthur | |

|---|---|

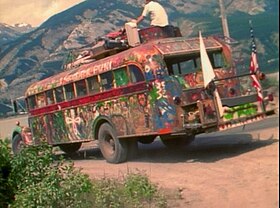

Ken Kesey's original Furthur in 1964 | |

| Overview | |

| Type | School bus |

| Manufacturer | International Harvester |

| Production | 1939 |

| Assembly | United States |

Furthur is a 1939 International Harvester school bus purchased by author Ken Kesey in 1964 to carry his "Merry Band of Pranksters" cross-country, filming their counterculture adventures as they went. The bus featured prominently in Tom Wolfe's 1968 book The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test but, due to the chaos of the trip and editing difficulties, footage of the journey was not released as a film until the 2011 documentary Magic Trip.

History

[edit]Kesey traveled to New York City in November 1963 with his wife Faye and Prankster George Walker to attend the Broadway opening of One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, which was based on his 1962 novel. Kesey also saw the 1964 New York World's Fair site under construction. He needed to return to New York City in 1964 for the publication party for his novel Sometimes a Great Notion, and hoped to use the occasion to visit the Fair. This plan grew into an ambitious scheme to bring along a group of friends, turning their adventures into a road movie, taking inspiration from Jack Kerouac's 1957 novel On the Road.

As more Pranksters volunteered for the trip, they soon realized they outgrew Kesey's station wagon, so Kesey bought a retired yellow school bus for $1,250 from Andre Hobson of Atherton, California. The license plates read "MAZ 804". Hobson had added bunks, a bathroom, and a kitchen with refrigerator, and stove for taking his eleven children on vacation.

The Pranksters added customizations, including a generator, a sound system (with an interior and external intercom), a railing and seating platform on top of the bus, and an observation turret coming out the top made from a washing machine drum fitted into a hole in the roof. Another platform was welded to the rear to hold the generator and a motorcycle. The bus was painted by the various Pranksters in a variety of psychedelic colors and designs. The paint was not day-glo (which was not yet common in 1964) but primary colors, and the peace symbol was not yet evident. The word 'Sunshine' was written in blue, but it was too early to have references to orange sunshine LSD or Kesey's not-yet-conceived daughter Sunshine.

The bus was named by artist Roy Sebern, painting the word "Furthur" (with two U's, quickly corrected) on the destination placard as a kind of one-word poem and inspiration to keep going whenever the bus broke down. The misspelled name is still often used, as in Wolfe's book.

The original bus's last journey was a trip to the Woodstock Festival in 1969. After its historic trips, the bus was gutted and used around the Keseys' farm in Oregon until at least 1983. It was mentioned and pictured in an article in the May–June Saturday Review. It was eventually parked in the swamp on Kesey's Farm and gradually returned to the elements, until it was dragged out of the swamp with a tractor and stored in a farm warehouse.

Participants

[edit]The list of participants is undocumented. They took the general name "Merry Band of Pranksters" shortened to Merry Pranksters, but many Pranksters chose not to go, and others became Pranksters only because they chose to go.

Chloe Scott (founder of the Dymaxion Dance Group in 1962, age about 39) only lasted a day, because the chaos was too much for her. Cathy Casamo, friend of Mike Hagen, joined at the last minute, hoping to star in the movie they were supposedly making, but she was left behind in Houston.[1] Neal Cassady showed up at the last minute and displaced Roy Sebern as driver, as far as New York state. Ken Babbs probably did not plan to venture past his San Juan Capistrano home. Merry Prankster and author Lee Quarnstrom documents events on the bus in his memoir, When I Was a Dynamiter!

Jane Burton, George Walker, Steve Lambrecht, Paula Sundsten (Gretchen Fetchin), Sandy Lehmann-Haupt (sound engineer, younger brother of Christopher, and important source for Tom Wolfe's account [2]), Page Browning, Ron Bevirt (photographer and bookstore owner), and siblings Chuck Kesey, Dale Kesey, and John Babbs are also named as participants.

The group decided to dress in red, white, and blue stripes (so they could claim to be loyal patriots), maybe with distinctive patterns so they'd be easier for future film-goers to tell apart. They brought a Confederate flag, too. Their haircuts were conservative; long hair came into fashion with the Beatles.

Tom Wolfe's book gives the misleading impression he was a participant (he met Kesey the following year). Carolyn "Mountain Girl" Adams Garcia (not present) is often confused with Cathy Casamo. Kesey's wife Faye is sometimes included, and Furthur-painter Roy Sebern. Robert Stone met them briefly in New York city.

Drugs

[edit]Kesey had a generous supply of the then-legal psychedelic drug LSD, and they reportedly also took 500 Benzedrine pills (speed), and a shoebox full of rolled marijuana cigarettes.[3]

They were stopped several times by the government, but explained they were filmmakers. Until 1965, drug use received too little media attention for officials to be suspicious.

The first trip

[edit]Beat writer Neal Cassady was at the wheel on their maiden voyage from La Honda, California to New York (Sebern says he was their designated-driver before Cassady). They left on June 17, 1964, but because of various vehicle problems, it took them 24 hours to go the first 40 miles (64 km). George Walker recalls, "We left La Honda on June 14, 1964, about 3pm First stop, on Kesey's bridge, out of gas! Made it about 100 feet."

Their route took them first to San Jose, California, then Los Angeles. Chloe Scott bailed in San Jose, and Cathy Casamo joined them. They spent two days at Ken Babbs' home in San Juan Capistrano, painting his swimming pool (one version claims he joined at that point.)

Outside Wikieup, Arizona they got stuck in the sand by a pond, and had an intense LSD party while waiting for a tractor to pull them out. In Phoenix, they confounded the Barry Goldwater presidential headquarters by painting "A VOTE FOR BARRY IS A VOTE FOR FUN!" above the bus windows on the left side, and driving backward through the downtown. Casamo apparently took too much LSD in Wikieup, and spent much of the drive from Phoenix to Houston standing naked on the rear platform, to the amusement of the truckers following Furthur down the highway.

In Houston, they visited the Houston Zoo, then author Larry McMurtry's suburban home. Casamo's antics led to her being briefly institutionalized, so the Pranksters left her behind, and another friend drove her back home (Kesey's Further Inquiry wrestles with his enduring guilt about these events.)

In New Orleans, Cassady showed them the nightlife, then the Pranksters accidentally went swimming in a 'blacks only' area on Lake Pontchartrain.

Their next destination was Pensacola, Florida to visit a friend of Babbs, then up the east coast to New York City, arriving around June 29.

New York

[edit]In New York, they picked up novelist Robert Stone (who recounted his viewpoint in his 2007 book Prime Green). They reunited with Chloe Scott, and staged a party at her apartment, attended by Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg. They also visited the World's Fair. Ginsberg arranged a visit with LSD enthusiasts Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert in Millbrook, New York, but the West Coast style of partying was too wild for the Millbrook academics.

Their route home, without Cassady to drive, took them through Canada. They arrived back in La Honda in August.

Aftermath

[edit]Kesey and Babbs took on the frustrating challenge of editing over 100 hours of silent film footage and separate (unsynchronized) audio tapes.[4] They previewed their progress at regular open parties every weekend at Kesey's place, evolving into the 'Acid Tests' with live music from the Grateful Dead (known first as the Warlocks).

Tom Wolfe used the film and tapes as the basis of his book, but Kesey's edit was never finished or released, in part because Kesey was arrested in 1965 for marijuana possession (LSD would not become illegal until October 1966). Director Alex Gibney finally publicly released a major new edit in 2011 as the documentary Magic Trip.

Other trips

[edit]Other Furthur trips included an anti-Vietnam war rally in 1966 and Woodstock and Texas International Pop Festivals, both in 1969 (without Kesey). A race between Furthur and three buses from Wavy Gravy's Hog Farm is recounted in the July 1969 Whole Earth Catalog. More can be read about the adventures of the Merry Pranksters on Furthur in Tom Wolfe's 1968 book The Electric Kool Aid Acid Test, for which a movie directed by Gus Van Sant is in development.[5]

Second bus

[edit]

In 1990 Kesey created a second Further/Furthur, this one from a 1947 International Harvester bus. The second bus is labeled "Further" on the front and "Furthur" on the back. It is not called Furthur 2, and is not meant as a replica, although confusion between the two buses is intentional. The bus was created to coincide with the publication of Kesey's memoirs about the 1964 trip, entitled The Further Inquiry (ISBN 0670831743).[6][7][8]

The original 1964 Furthur was eventually dragged out of the swamp with a tractor and now resides in a warehouse at Kesey's farm in Oregon, alongside the 1990 Further.

Smithsonian Caper

[edit]The "Great Smithsonian Caper" was a prank perpetrated on the media. Reporters and journalists came to the farm while Kesey and friends were painting the new bus, and later, broadcast "Ken Kesey restored the original Furthur and is taking it to the Smithsonian." The next morning, a variety of national media were asking to "come along on the trip to the Smithsonian." The media rode along on Furthur for about a week, believing it was the original bus and it was donated to the museum.[9][10][11]

Apple party

[edit]In 1993, Kesey drove the second bus to California to speak at a private party hosted by Apple Computer. Apparently, the party producers claimed no knowledge of his history or politics, and after his drug references, they removed him from the stage. Then, they blocked the bus from leaving the parking lot, so Kesey schmoozed around the event until it ended.[12]

Restoration

[edit]The second Furthur bus was refurbished and toured the country as part of a "Furthur 50th Anniversary Trip" in the summer of 2014.[13][14][15] This trip was documented for the 2016 documentary film Going Furthur.[16][17]

Cultural significance

[edit]The cross-country trip of Furthur and the activities of the Merry Pranksters, with the success of Wolfe's book and other media accounts, led to a number of psychedelic buses appearing in popular media over the next few years, including in the Beatles' Magical Mystery Tour (1967 film), Medicine Ball Caravan (1971) and The Muppet Movie (1979 film).[18] A similar bus was created for the 1990 film Flashback.[19] The bus appears as inspiration for the cover and in the Amazon short story "Existential Trips" by William Bevill. Both Kesey and original Prankster Ken Babbs released books in 1990 recounting their famous adventure (Kesey's was called The Further Inquiry (ISBN 0670831743) and Babbs' was On the Bus (ISBN 0938410911)).

In the 2007 film, Across the Universe, a fictionalized version of the bus appears, this one a Chevrolet bearing the name "Beyond" in place of "Furthur". The bus also figures obliquely as a "technicolor motor home" in the Steely Dan song "Kid Charlemagne" (1976), about another LSD proponent, Owsley Stanley.[citation needed] The G4 original television show Code Monkeys (2007) references the bus in the first episode of the second season: a character voiced by Tommy Chong tells the legend of Chester Hopperpot, a psychedelic pioneer touring the country in a magical hippie bus called Farther. Ken Kesey's quote "You're either on the bus or off the bus," as quoted by Tom Wolfe, is often repeated as a counter-culture slogan. In the Grateful Dead song "The Other One", Bob Weir sings the lyric "the bus came by and I got on, that's when it all began, there was cowboy Neal at the wheel of the bus to never ever land", an apparent reference to the original Furthur.[20]

References

[edit]- ^ "The Magic Bus - Ken Kesey, Neal Cassady, Cathy Casamo and the Merry Pranksters". cathryncasamo.com. Archived from the original on June 6, 2023.

- ^ Martin, Douglas (3 November 2001). "Sandy Lehmann-Haupt, 59, One of Ken Kesey's Busmates". The New York Times.

- ^ Dodgson, Rick (2013). It's All a Kind of Magic: The Young Ken Kesey. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 132. ISBN 978-0299295134.

- ^ Eagan, Daniel (August 4, 2011). "Ken Kesey's Pranksters Take to the Big Screen". Smithsonian Magazine.

- ^ The Ultimate Trip: "Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test" Heads to the Big Screen, Rolling Stone, 2009-04-10

- ^ "THE FURTHER INQUIRY | Kirkus Reviews" – via www.kirkusreviews.com.

- ^ "Book Review: The Further Inquiry by Ken Kesey". wild-bohemian.com.

- ^ "The Further Inquiry". www.goodreads.com.

- ^ Ed McClanahan and the Merry Prankster Bus Reunion Tour, Interview with Ed McClanahan. September 22, 1994

- ^ "Kesey's Merry Prank: Bus Isn't the Original -- Smithsonian Says It Doesn't Want '47 Model".

- ^ Further On! True Facts About The Smithsonian Caper. Zane Kesey.

- ^ "Fun_People Archive - 20 May - Apple's Bad Trip". www.langston.com.

- ^ "Furthur Bus 50th Anniversary "Trip"". Kickstarter.

- ^ Ken Kesey’s original magic bus being restored. MSNBC (2006-01-20). Retrieved on 2012-07-15.

- ^ Barnard, Jeff (9 January 2006). "Kesey's bus on magic road to resurrection (Associated Press)". The Seattle Times. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

- ^ "The bus that started a movement". BC Local News. May 18, 2016.

- ^ "Going Further: An Interview with Filmmaker Lindsay Kent | Reality Sandwich". realitysandwich.com. 8 August 2016.

- ^ Strohl, Daniel (February 28, 2014). "The enduring influence of Ken Kesey's Furthur". Hemmings Motor News. Retrieved September 22, 2021.

- ^ "Flashback (1990)". American Film Institute. Retrieved September 22, 2021.

- ^ "The Other One". dead.net. 20 March 2007.

Furthur reading

[edit]- Ken Kesey, The Further Onquiry. Viking, 1990. ISBN 0-670-83174-3.

- William Bevill, Existential Trips. Amazon, 2020. ASIN B08G44J7PL.