Candlestick Park

"The Stick" | |

| |

| |

| Former names | Harney Stadium (1956–1959) Candlestick Park (1960–1995, 2008–2013) 3Com Park at Candlestick Point (1995–2002) San Francisco Stadium at Candlestick Point (2002–2004) Monster Park (2004–2008) |

|---|---|

| Address | 602 Jamestown Avenue |

| Location | San Francisco, California |

| Coordinates | 37°42′49″N 122°23′10″W / 37.71361°N 122.38611°W |

| Public transit | |

| Owner | City and County of San Francisco |

| Operator | San Francisco Recreation & Parks Department |

| Capacity | 43,765 (1960) 63,000 (Baseball) 69,732[5] (Football) |

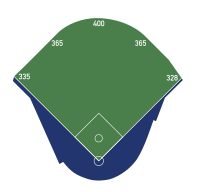

| Field size | Left field 330 ft (1960), 335 ft Left-center field & Right-center field 397 ft (1960), 365 ft[6] Center field 420 ft (1960), 400 ft Right field 330 ft (1960), 328 ft Backstop 73 ft (1960), 66 ft  |

| Surface | Bluegrass (1960–1969, 1979–2013) AstroTurf (1970–1978) |

| Construction | |

| Broke ground | August 12, 1958[1] |

| Opened | April 12, 1960 |

| Closed | August 14, 2014 |

| Demolished | February 4 – September 24, 2015 |

| Construction cost | US$15 million ($154 million in 2023 dollars[2]) |

| Architect | John Bolles & Associates |

| Structural engineer | Chin and Hensolt, Inc.[3] |

| General contractor | Charles Harney Co.[4] |

| Tenants | |

| San Francisco Giants (MLB) (1960–1999) San Francisco 49ers (NFL) (1971–2013) Oakland Raiders (AFL) (1960–1961) San Francisco Golden Gate Gales (USA) (1967) | |

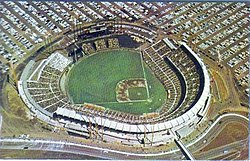

Candlestick Park was an outdoor stadium on the West Coast of the United States, located in San Francisco's Hunters Point area. The stadium was originally the home of Major League Baseball's San Francisco Giants, who played there from 1960 until 1999, after which the Giants moved into Pacific Bell Park (since renamed Oracle Park) in 2000. It was also the home field of the San Francisco 49ers of the National Football League from 1971 through 2013. The 49ers moved to Levi's Stadium in Santa Clara for the 2014 season. The last event held at Candlestick was a concert by Paul McCartney in August 2014, and the demolition of the stadium was completed in September 2015. As of 2019, the site is planned to be redeveloped into office space.[7]

The stadium was situated at Candlestick Point on the western shore of San Francisco Bay. Candlestick Point was named for the "candlestick birds" (long-billed curlews) that populated the area for many years. Due to Candlestick Park's location next to the bay, strong winds often swirled down into the stadium, creating unusual playing conditions. At the time of its construction in the late 1950s, the stadium site was one of the few pieces of land available in the city that was suitable for a sports stadium, and had room for the 10,000 parking spaces that had been promised to the Giants.

The surface of the field for most of its existence was natural bluegrass, but for nine seasons, from 1970 to 1978, the stadium had artificial turf. A "sliding pit" configuration, with dirt cut-outs only around the bases, was installed in 1971, primarily to keep the dust down in the breezy conditions. Following the 1978 football season, the playing surface was restored to natural grass.

Park history

[edit]When the New York Giants arrived in San Francisco in 1958, they played their home games at the old Seals Stadium at 16th and Bryant Streets. As part of the agreement regarding the Giants' relocation to the West Coast, the city of San Francisco promised to build a new stadium for the team. Most of the land at Candlestick Point was purchased from Charles Harney, a local contractor. Harney purchased the land in 1952 for a quarry and industrial development. He made a profit of over $2 million when he sold the land for the stadium. Harney received a no-bid contract to build the stadium. The entire deal was the subject of a grand jury investigation in 1958.

Ground was broken in 1958 for the stadium and the Giants selected the name of Candlestick Park, after a name-the-park contest on March 3, 1959 (for the derivation of which, see below). Prior to the choice of the name, its construction site had been shown on maps as the generic Bay View Stadium.[8] It was the first modern baseball stadium, as it was the first to be built entirely of reinforced concrete.[9] Then-Vice President Richard Nixon threw out the ceremonial first pitch on the opening day of Candlestick Park on April 12, 1960, and the Oakland Raiders played the final three games of the 1960 season[10] and their entire 1961 American Football League season at Candlestick Park. With only 77 home runs hit in 1960 (46 by Giants, 31 by visitors), the fences were moved in, from left-center to right-center, for the 1961 season.[6]

Following the 1970 season, the first with AstroTurf, Candlestick Park was enclosed, with grandstands around the outfield. This was in preparation for the 49ers in 1971, who were moving from their long-time home of Kezar Stadium. The result was that the wind speed dropped marginally, but often swirled irregularly throughout the stadium, and the view of San Francisco Bay was lost.

Candlestick Park played host to two Major League Baseball All-Star Games in its life as home for the Giants. The stadium hosted the first of two games in 1961 and later hosted the 1984 All-Star Game. The Giants played a total of six postseason series at Candlestick Park; they played host to the NLCS in 1971, 1987, and 1989, the World Series in 1962 and 1989, and one NLDS in 1997.

The 49ers hosted eight NFC Championship games during their time at Candlestick Park. The first was in January 1982 when Dwight Clark caught a game-winning touchdown pass from Joe Montana to lead the 49ers to Super Bowl XVI by defeating the Dallas Cowboys. Clark's play went down as one of the more famous in football history, and was dubbed "The Catch". The last of these came in January 2012, when Lawrence Tynes kicked a field goal in overtime to defeat the 49ers and send the New York Giants to Super Bowl XLVI. The final postseason game hosted by the 49ers at Candlestick Park was the 2012 NFC Divisional Playoff matchup between the 49ers and the Green Bay Packers, won by the 49ers by a score of 45–31. The 49ers' record in NFC Championship games at Candlestick Park was 4-4; they defeated the Cowboys twice, in 1981 and 1994, the Chicago Bears in 1984, and the Los Angeles Rams in 1989. Their losses came against the Cowboys in 1992, the Giants in 1990 and 2011, and the Packers in 1997.

In addition to Clark's famous touchdown catch, two more plays referred to as "The Catch" took place during games at Candlestick Park. The play dubbed "The Catch II" came in the 1998 NFC Wild Card round, as Steve Young found Terrell Owens for a touchdown with eight seconds left to defeat the two-time defending NFC Champion Packers. The play called "The Catch III" came in the 2011 NFC Divisional Playoffs, when Alex Smith threw a touchdown pass to Vernon Davis with nine seconds remaining to provide the winning margin against the New Orleans Saints.

On October 17, 1989, the Loma Prieta earthquake (magnitude 6.9) struck San Francisco, minutes before Game 3 of the World Series was to begin at Candlestick Park. No one within the stadium was injured, although minor structural damage was incurred to the stadium. Al Michaels and Tim McCarver, who called the game for ABC, later credited the stadium's design for saving thousands of lives.[9] An ESPN documentary about the earthquake revealed that the local stadium authority demanded that Candlestick Park undertake a major engineering project to shore up perceived safety red flags in the stadium. The authority pushed reluctant officials to get this done between the 1988 and 1989 baseball seasons, which prevented a "collapse wave" that could have killed thousands of fans and led to there being very few casualties of any kind in Candlestick Park after such a massive natural disaster. The World Series between the Giants and their Bay rivals the Oakland Athletics was subsequently delayed for 10 days, in part to give engineers time to check the stadium's overall structural soundness (and that of the Athletics' nearby home, the Oakland–Alameda County Coliseum). During this time, the 49ers moved their game against the New England Patriots on October 22 to Stanford Stadium, where they had defeated the Miami Dolphins 38–16 to win Super Bowl XIX on January 20, 1985.

The NFL awarded Super Bowl XXXIII to Candlestick Park on November 2, 1994.[11] After planned renovations in preparation for the game were not made, the NFL owners instead awarded Super Bowl XXXIII to the Miami area during their meeting on October 31, 1996. The league promised to award Super Bowl XXXVII following construction of a new football stadium, which was approved by voters in 1997, but the forced sale of the team by owner Eddie DeBartolo Jr. caused plans to fall through.[12]

In 2000, the Giants moved to the new Pacific Bell Park (now called Oracle Park) in the China Basin neighborhood, leaving the 49ers as the sole professional sports team to use Candlestick Park. The final baseball game was played on September 30, 1999, against their long-time rivals, the Los Angeles Dodgers, who won 9–4. In that game, all nine Dodgers starters had at least one base hit, while the stadium's final home run came from Dodgers' right fielder Raúl Mondesí in the 6th inning. The National League rivalry between the Giants and Dodgers, one of the oldest and most hotly contested in the Major Leagues, dated back to when both teams were based in New York City. When first the Dodgers, then the Giants, moved to California in 1958, the rivalry continued unabated.

For its last several years as home to just the 49ers, Candlestick Park was the only remaining NFL stadium to have begun as a baseball-only facility which later underwent an extensive redesign to accommodate football. That was evidenced by the stadium's curiously oblong and irregular shape, whereby views from a sizable section of lower-deck seating in the baseball configuration's right-field corner were so badly obstructed by the eastern grandstand of the football seating configuration that they were unusable for football games and would consequently sit empty. Since a football gridiron, including its end zones and benches along the sidelines, is much smaller than a baseball playing field and foul territory, this large grandstand, which provided thousands of prime seats along one whole sideline of the football field, was designed to be retractable. It would slide backwards for baseball games, under the upper deck, and provide a smaller section of baseball seating beyond the outfield wall in right. After the Giants played their 1999 season and moved away from Candlestick, this grandstand was left permanently in its football position, and the unusable seats were eventually removed.

On September 3, 2011, Candlestick Park hosted the first and only college football game in its history with a neutral site game between the California Golden Bears and Fresno State Bulldogs (Cal was designated the "home" team).[13][14] This game was in San Francisco, because of the massive renovation and seismic retrofit at California's home stadium, California Memorial Stadium. The rest of the Golden Bears' home games in 2011 were played at AT&T Park. Cal won the game 36–21.[15]

At approximately 5:19 p.m. local time on December 19, 2011, Candlestick Park experienced an unexpected power outage just before a Monday Night Football game between the 49ers and the Pittsburgh Steelers. An aerial shot shown live on ESPN showed a transformer sparking and then the stadium going completely dark. About 17 minutes later, however, the park's lights came back on in time for the game's kickoff. With 12:13 remaining in the second quarter, another power outage created yet another 30-minute delay before play resumed again. The 49ers 2011 season ended at Candlestick Park with a loss to the New York Giants in the NFC Championship Game.

The 49ers played their final game at Candlestick Park on Monday, December 23, 2013, against the Atlanta Falcons, winning 34–24 after a NaVorro Bowman interception that would be called The Pick at the Stick by some sports columnists.[16] This game was the facility's 36th and final game on Monday Night Football,[17] the most at any stadium used by the NFL.[18]

Reputation

[edit]As a baseball field, the stadium was infamous for the windy conditions, damp air and dew from fog, and chilly temperatures. The wind often made it difficult for outfielders trying to catch fly balls, as well as for fans, while the damp grass further complicated play for outfielders who had to play in cold, wet shoes. Architect John Bolles designed the park with a boomerang-shaped concrete baffle in the upper tier in order to protect the park from wind. Unfortunately, it never worked properly. For Candlestick's first 10 seasons, the wind blew in from left-center and out toward right-center. When the park was expanded to accommodate the 49ers in 1971, it was thought that fully enclosing the park would cut down on the wind significantly. Instead, the wind swirled from all directions, and was as strong and cold as before. Giants Hall of Fame center fielder Willie Mays claimed the wind cost him over 100 home runs. (It may be noted that in the 12 years he played at Candlestick Park, from 1960 through 1971, Mays hit 396 home runs, 203 at Candlestick and 193 on the road.[19]) Nonetheless, he had less difficulty fielding balls in the windy conditions. Mays was used to playing in difficult and absurdly sized field conditions, beginning his career at the Polo Grounds in New York, which featured an enormous outfield where he made a famous World Series-saving catch.

During the first All Star Game of 1961 (one of two played in the park—the other was in 1984), Giants pitcher Stu Miller was blown off balance by a gust of wind and was charged with a balk.[20] Two years later, wind picked up the entire batting cage and dropped it 60 feet (18 m) away on the pitcher's mound while the New York Mets were taking batting practice.

The stadium also had the reputation as the coldest park in Major League Baseball, with winds blowing directly off the Pacific Ocean. It was initially built with a radiant heating system of hot water pipes under the lower box seats in a space between the concrete and the ground. The pipes were not embedded in the concrete, however, and did not produce enough heat to offset the cold air. Both the city and the Giants balked at the cost of upgrading the system so it would work properly, which would have involved removing the seats and concrete, embedding larger pipes, and replacing the concrete and seats. As a result, the Giants played more day games than any Major League Baseball team except the Chicago Cubs, whose ballpark, Wrigley Field, did not have lights installed until 1988. Many locals, including Giants' broadcaster Lon Simmons, were surprised at the decision to build the park right on the bay, in one of the coldest areas of the city.[9] Attorney Melvin Belli filed a claim against the Giants in 1960 because his six-seat box, which cost him almost $1,600, was unbearably cold. Belli won in court, claiming that the "radiant heating system" advertised was a failure.[21]

The Giants eventually played on the reputation to bolster fan support with humorous promotions such as awarding the 'Croix de Candlestick' pin to fans who stayed for the duration of extra-inning night games. The pins featured the Giants' "SF" monogram capped with snow, along with the Latin slogan "Veni, vidi, vixi" ("I came, I saw, I survived"). Among many less-than-flattering fan nicknames for the park were "North Pole", "Cave of the Winds", "Windlestick", "The Quagmire", and "The Ashtray By The Bay". Older fans called it "The Dump" in honor of the former use of the land. Ironically, the Giants played their last night game at Candlestick (against the Los Angeles Dodgers) on September 29, 1999, under clear skies and a game time temperature of 74°[22] as well as their last day game at Candlestick on September 30, 1999, under blue skies with no fog and a game time temperature of 82°, all of which was common for September games.

Giants owner Horace Stoneham visited the site as early as 1957 and was involved in the stadium's design from the outset. While he was aware of the weather conditions, he usually visited the park during the day, not knowing about the particularly cold, windy and foggy conditions that overtook it at night. Originally, Bolles' concrete baffle would have extended all the way to left field, which would have further reduced the prevailing winds. Nevertheless, the size of the structure was reduced for cost savings. In 1962, Stoneham commissioned a study of the wind conditions. The study revealed that had the windy conditions been known prior to construction, conditions would have been significantly improved by building the park 100 yards farther to the north and east.[9][23] This would have meant building it on fill, however, which is less stable during earthquakes. The stadium's location on the bedrock of Bayview Hill provided more stability.

The winds were intense in the immediate area of the park. Studies showed they were no more frequent than other parts of San Francisco but are subject to higher gusts. This is because of a hill immediately adjacent to the park. This hill, in turn, is the first topographical obstacle met by the prevailing winds arriving from the Pacific Ocean 7 miles (11 km) to the west. Arriving at Candlestick from the Pacific, these winds travel through what is known as the Alemany Gap before reaching the hill. The combination of ocean winds free-flowing to Candlestick, then swirling over the adjacent hill, created the cold and windy conditions that were the bane of the Giants' 40-year stay on Candlestick Point. It was indeed the wind and not the ambient air temperature that provided Candlestick's famed chill. The Giants' subsequent home, Oracle Park, is just one degree warmer, but is far less windy, creating a "warmer" (relatively speaking) effect. While the wind is a summer condition (hot inland, cool oceanside), winter weather is right in line with the rest of sea level Northern California (mild with occasional rain).

Other design flaws and irregularities

[edit]Candlestick was an object of scorn from baseball purists for reasons other than weather. Although originally built for baseball, foul territory was quite roomy. According to Simmons, nearly every seat was too far from the field even before the 1971 expansion.[9] As with the radiant heating system in the grandstands, the heating systems in the dugouts were wholly inadequate. Players on other National League teams – especially if they had played for the Giants beforehand – complained that the visitors dugout was noticeably colder than the Giants' dugout. That was due to two factors. One was that the Giants' dugout included a tunnel to the clubhouse, so heat from the clubhouse flowed into the dugout. The other involved the placement of the dugouts. The Giants' dugout was located on the first base side, which was on the south side of the stadium. The visitors' dugout was located on the third base (west) side of the field.

Notable events

[edit]Concerts

[edit]| Date | Artist | Opening act(s) | Tour / Concert name | Attendance | Revenue | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| August 29, 1966 | The Beatles | 1966 US tour | 25,000 | — | An "official" bootleg recording of the 11-song, 33-minute setlist was made by the Beatles' press officer, Tony Barrow, at the request of the band. As his cassette could only record 30 minutes per side, it ran out in the middle of the closing song, "Long Tall Sally".[24] | |

| October 17, 1981 | The Rolling Stones | American Tour 1981 | 135,000 / 135,000 | $2,092,500 | ||

| October 18, 1981 | ||||||

| June 1, 1985 | Jimmy Buffett | — | Sleepless Knights Tour | — | — | |

| July 17, 1988 | Van Halen Scorpions |

Monsters of Rock Tour 1988 | — | — | A stadium-wide food fight took place aimed solely at the upper deck. Opening act Kingdom Come played for 45 minutes, Metallica and Dokken played for 60 minutes each, Scorpions played for 75 minutes, and Van Halen for 100 minutes. | |

| July 14, 2000 | Metallica | Summer Sanitarium Tour | — | — | ||

| August 10, 2003 | ||||||

| July 26, 2013 | Justin Timberlake Jay-Z |

DJ Cassidy | Legends of the Summer | 55,359 / 55,359 | $5,129,345 | |

| August 14, 2014 | Paul McCartney | — | Out There | 53,477 / 53,477 | $7,023,107 | The stadium's final concert.[25] |

The Beatles' final concert

[edit]The Beatles famously gave their last full public concert at Candlestick Park on August 29, 1966. Songs performed at the show were "Rock and Roll Music", "She's a Woman", "If I Needed Someone", "Day Tripper", "Baby's in Black", "I Feel Fine", "Yesterday", "I Wanna Be Your Man", "Nowhere Man", "Paperback Writer", and "Long Tall Sally".

An "official" bootleg recording of the 33-minute setlist was made by the Beatles' press officer, Tony Barrow, at the request of the band. As his cassette could only record 30 minutes per side, it ran out with a minute of the closing song, "Long Tall Sally", remaining.[24] This recording has never been officially released, although it has been leaked on to the internet.

At the time, The Beatles had not announced that this was to be their final concert, and even if the foursome themselves knew, it was a closely guarded secret. Much of the existing color film footage of the concert was captured by a 15-year-old Beatles fan, Barry Hood. A relatively small amount of black-and-white footage was shot by local TV news in the San Francisco Bay Area and Sacramento. Hood released some of his film in a limited edition documentary titled The Beatles Live In San Francisco,[26] but more of Hood's very rare footage remains in a vault, unseen by the public as of 2017.[26] On August 14, 2014, former Beatle Paul McCartney returned to become the closing act of Candlestick Park's long musical history. To showcase the event, McCartney contacted Barry Hood and used a portion of his original 1966 Beatles film on a big screen at this last concert.

Papal Mass

[edit]Pope John Paul II celebrated a Papal Mass on September 18, 1987, at Candlestick Park during his tour of America.[27][28] An estimated crowd of 70,000 attended the Mass.[29]

In popular culture

[edit]Candlestick Park was home to dozens of commercial shoots as well as the location for the climactic scene in both the 1962 thriller Experiment in Terror and the 1974 Richard Rush comedy Freebie and the Bean. The stadium was featured in the 1976 Dirty Harry movie, The Enforcer. The stadium was featured in the 1994 family comedy Getting Even with Dad, where the father character (played by Ted Danson) takes his son (played by Macaulay Culkin) to a San Francisco Giants game. The stadium was featured briefly in the 1996 action film The Rock where a missile almost attacks the place before being diverted away by the last second. In February 2011, scenes for the film Contagion, starring Matt Damon, Kate Winslet and Jude Law, were filmed at the stadium. The Fan was also filmed there in 1996. In 2010, Candlestick Park was featured as the finishing point for the finale of The Amazing Race 16. And 1989 World Series, The series was known for one of the sites of the 1989 San Francisco earthquake.[30]

Jackson, Mississippi landowner and developer Homer Lee Howie built a shopping center on Cooper Road in the city which opened in August 1963. Howie was originally going to name the shopping center Cooper Mart but one day watched the Giants on television at the stadium and thought the name Candlestick Park sounded catchy and would greatly help bring in customers and decided to name the center by that name without permission. The center was a popular shopping place and community center in southern Jackson for its first few years before being completely destroyed in the 1966 Candlestick Park tornado outbreak on March 3, 1966, which killed a total of 57 people, 12 of them in the shopping center. The center still exists today, but was never the same after the tornado.[31]

Seating capacity

[edit]

|

|

Name changes

[edit]

Some think that Candlestick Point was named for the indigenous "candlestick bird" (long-billed curlew), once common to the point.[32] The book "California Geographic Names" lists Candlestick Point as being named for a pinnacle of rock first noted in 1781 by the De Anza Expedition. This pinnacle was also noted by the U.S. Geodetic Survey in 1869. The pinnacle disappeared around 1920.

The rights to the stadium name were licensed to 3Com Corporation from September 1995 until 2002, for $900,000 a year. During that time, the park became known as "3Com Park at Candlestick Point", or, simply, "3Com Park". In 2002, the naming rights deal expired, and the park then became officially known as "San Francisco Stadium at Candlestick Point". On September 28, 2004, a new naming rights deal was signed with Monster Cable, a maker of cables for electronic equipment, and the stadium was renamed "Monster Park". Just over a month later, however, a measure passed in the November 2 election stipulated that the stadium name revert to "Candlestick" permanently after the contract with Monster expired in 2008.[33]

The City and County of San Francisco had trouble finding a new naming sponsor due in part to the downturn in the economy, but also because the stadium's tenure as 3Com Park was tenuous at best. Many local fans were annoyed with the change and continued referring to the park by its original name, regardless of the official name. The Giants reportedly continued to call the stadium "Candlestick Park" in media guides, because the naming rights were initiated by the 49ers. Some even mocked the 3Com sponsorship. Chris Berman, for instance, usually called it "Commercial-Stick Park". Local fans sometimes called it "Dot-com Park" (see Dot-com bubble). Freeway signs in the vicinity were changed to read "Monster Park" as part of an overall signage upgrade to national standards on California highways, but in 2008 those signs were changed back to "Candlestick Park".

The name change also ended up being confusing for the intended branding purposes, as without the "Cable" qualifier in the official name, many erroneously thought the stadium was named for the Monster.com employment website or Monster Energy Drink, not the cable vendor.[34]

On August 10, 2007, San Francisco mayor Gavin Newsom announced that the playing field would be renamed "Bill Walsh Field" in honor of the former Stanford and 49ers coach, who died on July 30 that year, pending the approval of the city government. The stadium itself retained its name as was contractually obligated.[35] Commentators still use this name occasionally, most recently when Jerry Rice's jersey was retired.

On September 18, 2009, Sports Illustrated's Peter King used the mock-combination name "Candle3Monsterstick" in reference to the many name changes the stadium has gone through.[36]

Despite numerous official and unofficial name changes over the history of the stadium and surrounding park/facilities, the stadium was lovingly referred to as "the Stick" by many locals and die-hard fans from its original titling of "Candlestick Park" in 1960.

Replacement and demolition

[edit]By 1997, plans were underway to construct a new 68,000-seat stadium at Candlestick Point.[37] On November 8, 2006, however, the 49ers announced that they would abandon their search for a location in San Francisco and begin to pursue the idea of building a stadium in Santa Clara. Because its centerpiece stadium was lost, San Francisco withdrew its bid for the 2016 Olympics on November 13, 2006. Ground-breaking for the Santa Clara stadium occurred on April 19, 2012. On May 8, 2013, the media announced that the name of the new stadium would be Levi's Stadium. The stadium opened on July 17, 2014, in time for the 2014 NFL season. The 49ers christened their new home a month after it opened.

A grassroots movement for the Giants to play another baseball game at Candlestick had existed since 2009. Many fans had hoped to see another game in 2010, the 50th anniversary of the Giants' first season at Candlestick Park, but the idea was dropped due to the cost. Although many fans wished for another Giants game at the Stick, the Giants never returned to their former stadium for a final game.

With the departure of the 49ers, Candlestick Park was left without any permanent tenants. Demolition was expected to occur soon after the 49ers played their final game of the 2013 season, but over time the date of demolition was moved back to late 2014, with several special events planned for the intervening period.[38] In April 2014, Paul McCartney announced that he would perform a concert as the last scheduled event in the 54-year-old stadium on August 14, 2014.[39] The Beatles had performed their last scheduled concert at Candlestick Park 48 years earlier.

Demolition began in November 2014 as workers tore out seats.[40] In January 2015, the developer withdrew a request to implode the stadium, possibly to be broadcast as part of the Super Bowl halftime entertainment. Instead, mechanized structural demolition commenced, which was favored over implosion due to local dust pollution concerns.[41] Demolition was expected to be complete by March 2015,[42][43] but was not completed until September 24, 2015.

In 2014, 1,000 historic Candlestick Park Stadium seats were installed at Kezar Stadium for the public to enjoy. The renovation was funded by the city's Capital Planning General Fund. Mayor Edwin M. Lee helped re-open the stadium with a warm-up run.[44]

In December 2016, 4,000 additional historic Candlestick seats were acquired and installed at Kezar. The seats were paid for by the San Francisco Deltas as a part of a $1-million improvement the team agreed upon to make use of the stadium.[45]

In November 2014, Lennar and Macerich announced plans to build a dense "urban outlet" center incorporating retail and housing with underground parking on the Candlestick Park site. The proponents suggested that the new development would be completed in 2017.[46] The project has not proceeded, and the plan was suspended by its proponents in April 2018.[47]

Croix de Candlestick

[edit]

The Croix de Candlestick is an award pin that was given out to baseball fans as they exited Candlestick Park at the conclusion of a night game that went extra innings.[48][49] In reference to the ballpark's legendarily cold winds, the pin carried the motto, "Veni, Vidi, Vixi" ("I came, I saw, I survived").[50]

In order to receive a pin, the fans would have to redeem their ticket stub for the pin at Patrick & Co. Stationery store in San Francisco. The pin, developed by team marketing director Patrick J. Gallagher, was first issued in 1983. In 1983 the San Francisco Giants played in five extra inning night games,[51] with a total attendance of 70,933 and in 1984 they played in five extra inning night games[52] with a total attendance of 44,031. The pin was given out for several years. On September 28–30, 1999, tens of thousands of fans received the pin for attending the Giants' final three-game home stand at Candlestick, against the team's archrival, the Los Angeles Dodgers.[53][54] A San Francisco Chronicle columnist later called it "the smartest marketing promotional in Bay Area history".[55]

The Croix de Candlestick received national exposure during the 1983 All-Star Game at Chicago's Comiskey Park. Giants pitcher Atlee Hammaker wore it on his cap and was mentioned by NBC announcer Joe Garagiola.

"Mayor Ed Lee...: I'm a real San Franciscan, because I've EARNED a Croix de Candlestick and whenever I hear the phrase "the catch" I have to take a moment..."[56]

"They don't give out a Croix de Candlestick to fans who stay 'til the bitter end at Levi's, or even a Croix de Fiddlesticks, but this time the late birds got their reward."[57]

References

[edit]- ^ Rosenbaum, Art (August 12, 1958). "Bay City Banner". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 7, 2012. Retrieved September 16, 2011.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ "City and County of San Francisco, Candlestick Park, San Francisco, CA (1958–1960)". Pacific Coast Architecture Database. Retrieved September 9, 2016.

- ^ Munsey, Paul; Suppes, Cory. "Candlestick Park". Ballparks.com. Retrieved September 9, 2016.

- ^ "2009 San Francisco 49ers Media Guide" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved July 24, 2010.

- ^ a b "Candlestick Park dimensions cut". Spokane Daily Chronicle. Washington. Associated Press. December 15, 1960. p. 45.

- ^ Li, By Roland (March 12, 2019). "Mall plan dead at SF's Candlestick Point, former home of Giants and 49ers". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ "Pot Luck". St. Petersburg Times. March 4, 1959. p. 3-C.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d e Smith, Curt (2001). Storied Stadiums. New York City: Carroll & Graf. ISBN 0-7867-1187-6.

- ^ "Raiders Face L.A. In 'Must' Game At Candlestick Park". Oakland Tribune. December 4, 1960. p. 57.

- ^ https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=OowyAAAAIBAJ&sjid=B-cFAAAAIBAJ&pg=2467,966185&dq=super-bowl+site&hl=en Lawrence Journal-World - Google News Archive Search

- ^ Stimson, Alex (May 23, 2023). "San Francisco was twice set to host the Super Bowl. Here's why it never happened". The Mercury News. Retrieved June 2, 2023.

- ^ Adelson, Andrea (May 17, 2011). "Jeff Tedford talks Fresno State ties". go.com. Retrieved September 9, 2016.

- ^ Crumpacker, John (August 26, 2011). "Fresno St. Drawing Better Than Cal for Opener". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved August 27, 2011.

- ^ "2011 Cal Bears Football Stats". calbears.com. 2012. Archived from the original on July 16, 2012. Retrieved September 9, 2016.

- ^ Maiocco, Matt (December 23, 2013). "Instant Replay: 49ers survive, punch playoff ticket in 'Stick finale". CSN Bay Area. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved September 9, 2016.

- ^ "Atlanta Falcons at San Francisco 49ers - December 23rd, 2013". Pro-Football-Reference.com. Retrieved September 9, 2016.

- ^ Fairburn, Matthew (December 24, 2013). "49ers vs. Falcons provides final classic Monday Night Football moment at Candlestick Park". SBNation.com. Retrieved September 9, 2016.

- ^ Baseball Reference. "Willie Mays".

- ^ "Stu Miller, All-Star Who Committed a Windblown Balk, Dies at 87". The New York Times. Associated Press. January 6, 2015. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ^ How Do Astronauts Scratch an Itch? by David Feldman

- ^ "Los Angeles Dodgers at San Francisco Giants Box Score, September 29, 1999".

- ^ Kareem, Ahsan (2006). "A Tribute to Jack E. Cermak" (PDF). JEC Wind Engineer. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 14, 2006. Retrieved September 9, 2016.

- ^ a b Runtagh, Jordan (August 29, 2016). "Remembering Beatles' Final Concert". Rolling Stone. Retrieved February 7, 2018.

- ^ Swartz, Jon (August 15, 2014). "Paul McCartney is Candlestick Park's closing act". USA Today. Retrieved September 9, 2016.

- ^ a b "Beatles Last Concert Candlestick Park San Francisco DVD". televideos.com. Retrieved September 9, 2016.

- ^ Nolte, Carl (September 18, 1987). "Pope in S.F.: When John Paul II blessed AIDS sufferers". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved February 7, 2018.

- ^ Dugan, Barry W. (September 23, 1987). "Local faithful among throng at Candlestick for Pope's visit". Healdsburg Tribune, Enterprise and Scimitar. Retrieved February 7, 2018.

- ^ Hartlaub, Peter (June 6, 2013). "A Pray on the Green: The Pope at Candlestick in 1987". The Big Event [blog]. San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved February 7, 2018.

- ^ Franich, Darren (May 10, 2010). "The Amazing Race season finale recap: If You're Going to San Francisco". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved January 6, 2020.

- ^ Clarion Ledger, Jackson (MS), February 27, 2006, page 80

- ^ Hatfield, Larry D. (January 29, 2002). "Supervisor wants Candlestick to stick". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved September 9, 2016.

- ^ "Proposition H: Naming the Stadium at Candlestick Point - San Francisco County, CA". www.smartvoter.org.

- ^ Gardner, Jim (November 28, 2005). "Fans unclear on main Monster in 49ers lineup". San Francisco Business Times. Retrieved November 28, 2005.

- ^ "8,000 turn out at Monster Park to say goodbye to Bill Walsh". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved September 9, 2016.

- ^ "Fascinating matchup in San Diego, more to watch this weekend". SportsIllustrated. September 18, 2009. Retrieved July 31, 2023.

- ^ "A very different stadium plan". San Francisco Chronicle. July 18, 2006. Retrieved September 9, 2016.

- ^ Shafer, Margie (December 18, 2013). "Special Events Planned At Candlestick Park Before Demolition". San Francisco CBS local. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- ^ Matier, Phillip; Ross, Andrew (April 24, 2014). "Paul McCartney to play Candlestick's final show". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved April 28, 2014.

- ^ Matier, Phillip; Ross, Andrew (November 18, 2014). "Candlestick teardown begins — seats being ripped out". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved March 18, 2015.

- ^ Matier, Phillip; Ross, Andrew (January 16, 2015). "Candlestick Park will go out with a wrecking ball, not a bang". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved March 18, 2015.

- ^ Fernandez, Lisa (February 4, 2015). "Demolition of Candlestick Park Underway; New Development to Replace Old Stadium". NBC Bay Area. Retrieved March 18, 2015.

- ^ Rubenstein, Steve (February 5, 2015). "Last team at Candlestick Park is bent on demolition". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved March 18, 2015.

- ^ Mayor Ed Lee (March 17, 2015). "Mayor Lee at Kezar Track Opening After $3.2 Million Renovation". Archived from the original on November 7, 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Candlestick seats will soon fill SF's Kezar Stadium, thanks to Deltas soccer team". December 2, 2016.

- ^ Dineen, J. K. (November 17, 2014). "Major 'urban outlet' retail center planned for Candlestick Point". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ Li, Roland; Burke, Katie (April 6, 2018). "Exclusive: FivePoint suspends work on 635,000-square-foot shopping mall at the former Candlestick Park". American City Business Journals.

- ^ "Croix de Candlestick". Welcome to Third and King. May 9, 2008.

- ^ "Yahoo Sports MLB". sports.yahoo.com.

- ^ Chris Ballard, "Candlestick Park, 1960−2013", Sports Illustrated, December 30, 2013.

- ^ "1983 San Francisco Giants Schedule". Baseball-Reference.com.

- ^ "1984 San Francisco Giants Schedule". Baseball-Reference.com.

- ^ David Steele, "The Last Night Resembled Very Few Others", San Francisco Chronicle, September 30, 1999.

- ^ "Candle In The Wind", Los Angeles Times, September 28, 1999.

- ^ Hartlaub, Peter (August 18, 2010). "The badges of honor of a Bay Area resident". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ Spotswood, Beth (February 1, 2012). "When Can You Call Yourself A Native?". Culture Blog!.

- ^ Ostler, Scott (November 26, 2017). "49ers' Jimmy Garoppolo provides reason for excitement". San Francisco Chronicle.

External links

[edit]- www.ballparks.phanfare.com photos and info about Candlestick park

- Sports Illustrated cover – July 18, 1960

- Photos of demolition in progress, May 2015

- Gallery of images from the park's history

| Events and tenants | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by | Home of the San Francisco 49ers 1971–2013 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | Home of the San Francisco Giants 1960–1999 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | Host of the MLB All-Star Game 1961 1984 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | Home of the Oakland Raiders 1961 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | Host of NFC Championship Game 1982 1985 1990–1991 1993 1995 1998 2012 |

Succeeded by |

- Candlestick Park

- American football venues in California

- Baseball venues in California

- Sports venues in San Francisco

- Demolished sports venues in California

- Demolished buildings and structures in San Francisco

- Parks in San Francisco

- American football venues in San Francisco

- San Francisco 49ers stadiums

- San Francisco Giants stadiums

- American Football League venues

- Defunct American football venues in the United States

- Defunct baseball venues in the United States

- Defunct Major League Baseball venues

- Defunct National Football League venues

- Oakland Raiders stadiums

- Soccer venues in San Francisco

- Sports venues completed in 1960

- Sports venues destroyed in 2015

- 1960 establishments in California

- 2015 disestablishments in California

- 20th century in San Francisco

- Music venues in San Francisco