Abdullah Öcalan

Abdullah Öcalan | |

|---|---|

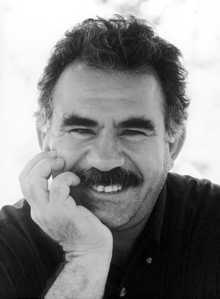

Öcalan in 1997 | |

| Born | 4 April 1949[1] Ömerli, Turkey |

| Nationality | Kurdish[2][3][4][5][6] |

| Citizenship | Turkey |

| Education | Faculty of Political Science, Ankara University[7] |

| Occupations | Founder and leader of militant organization PKK,[8] political activist, writer, political theorist |

| Organization(s) | Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK), Kurdistan Communities Union (KCK) |

| Spouse |

Kesire Yıldırım (m. 1978) |

| Relatives |

|

Philosophy career | |

Notable ideas | |

Abdullah Öcalan (/ˈoʊdʒəlɑːn/ OH-jə-lahn;[9] Turkish: [œdʒaɫan]; born 4 April 1949), also known as Apo[9][10] (short for Abdullah in Turkish; Kurdish for "uncle"),[11][12] is a founding member of the militant Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK).[13][14]

Öcalan was based in Syria from 1979 to 1998.[15] He helped found the PKK in 1978, and led it into the Kurdish–Turkish conflict in 1984. For most of his leadership, he was based in Syria, which provided sanctuary to the PKK until the late 1990s.

After being forced to leave Syria, Öcalan was abducted by the Turkish National Intelligence Organization (MIT) in Nairobi, Kenya in February 1999 and imprisoned on İmralı island in Turkey,[16] where after a trial he was sentenced to death under Article 125 of the Turkish Penal Code, which concerns the formation of armed organizations.[17] The sentence was commuted to aggravated life imprisonment when Turkey abolished the death penalty. From 1999 until 2009, he was the sole prisoner[18] in İmralı prison in the Sea of Marmara, where he is still held.[19][20]

Öcalan has advocated a political solution to the conflict since the 1993 Kurdistan Workers' Party ceasefire.[21][22] Öcalan's prison regime has oscillated between long periods of isolation during which he is allowed no contact with the outside world, and periods when he is permitted visits.[23] He was also involved in negotiations with the Turkish government that led to a temporary Kurdish–Turkish peace process in 2013.[24]

From prison, Öcalan has published several books. Jineology, also known as the science of women, is a form of feminism advocated by Öcalan[25] and subsequently a fundamental tenet of the Kurdistan Communities Union (KCK).[26] Öcalan's philosophy of democratic confederalism is applied in the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES),[27] an autonomous polity formed in Syria in 2012.

Early life and education

Öcalan was born in Ömerli, a village in Halfeti, Şanlıurfa Province in eastern Turkey.[28] While some sources report his date of birth as 4 April 1949,[1] no official birth records exist. He has claimed not to know exactly when he was born, estimating the year to be 1946 or 1947.[29] He is the oldest of seven children.[30] He attended elementary school in a neighboring village and wanted to join the Turkish army.[31] He applied to the military high school but failed in the admission exam.[32] In 1966 he began to study at a vocational high school in Ankara (Turkish: Ankara Tapu-Kadastro Meslek Lisesi)[32] and attended meetings of anti-communists but also of circles active in left wing politics[33] interested in improving Kurdish rights.[32] He was also a very conservative Muslim in his youth and he admired Necip Fazıl Kısakürek.[34] After graduating in 1969, Öcalan began working at the Title Deeds Office of Diyarbakır. It was at this time his political affiliation began to take a form.[33] He was relocated one year later to Istanbul[32] where he participated in the meetings of the Revolutionary Cultural Eastern Hearths (DDKO).[35][36] Later, he entered the Istanbul Law Faculty but after the first year transferred to Ankara University to study political science.[37]

His return to Ankara was facilitated by the state in order to divide the Dev-Genç (Revolutionary Youth Federation of Turkey), of which Öcalan was a member. President Süleyman Demirel later regretted this decision, since the PKK was to become a much greater threat to the state than Dev-Genç.[38]

Öcalan was not able to graduate from Ankara University,[39] as on 7 April 1972 he was arrested after participating in a rally against the killing of Mahir Çayan.[33] He was charged with distributing the left-wing political magazine Şafak (published by Doğu Perinçek) and was held for seven months at the Mamak Prison.[40] In November 1973, the Ankara Democratic Association of Higher Education, (Ankara Demokratik Yüksek Öğrenim Demeği, ADYÖD) was founded and shortly after he was elected to join its board.[41] In the ADYÖD several students close to the political views of Hikmet Kıvılcımlı were active.[41] In December 1974, ADYÖD was closed down.[42] In 1975, together with Mazlum Doğan and Mehmet Hayri Durmuş, he published a political booklet which described the main aims for a Revolution in Kurdistan.[43] During meetings in Ankara between 1974 and 1975, Öcalan and others came to the conclusion that Kurdistan was a colony and preparations ought to be made for a revolution.[44] The group decided to disperse into the different towns in Turkish Kurdistan in order to set up a base of supporters for an armed revolution.[44] At the beginning, this idea had only a few supporters, but following a journey Öcalan made through the cities of Ağrı, Batman, Diyarbakır, Bingöl, Kars and Urfa in 1977, the group counted over 300 adherents and had organised about thirty armed militants.[44]

The Kurdistan Workers' Party

In 1978, in the midst of the right- and left-wing conflicts which culminated in the 1980 Turkish coup d'état, Öcalan founded the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK).[45] In July 1979 he fled to Syria.[46]

Since its foundation, the party focused on ideological training.[47] Marxism-Leninism, the history and estate of Kurdistan had a central role in the party.[47] Öcalan elaborated on the importance of ideology to the extent to where he condemned ideologylessness and equated ideology with religion which according to him had replaced the latter.[47] "If you break the link between yourself and ideology you will beastialize".[48] With the support of the Syrian Government, he established two training camps for the PKK in Lebanon where the Kurdish guerrillas should receive political and military training.[43]

In 1984, the PKK initiated a campaign of armed conflict by attacking government forces[49][50][51] in order to create an independent Kurdish state. Öcalan attempted to unite the Kurdish liberation movements of the PKK and the one active against Saddam Hussein in Iraq. In negotiations between the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the PKK, it was agreed that the latter was able to move freely in Iraqi Kurdistan. He also met twice with Masoud Barzani, the leader of the KDP in Damascus, to resolve some minor issues they had once in 1984 and another time in 1985. But due to pressure from Turkey the cooperation remained timid.[52] During an interview he gave to the Turkish Milliyet in 1988, he mentioned the goal wasn't to gain independence from Turkey at all costs, but remained firm on the issue of the Kurdish rights, and suggested that negotiations should take place for a federation to be established in Turkey.[53] In 1988, he also met with Jalal Talabani of the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) in Damascus, with which he signed an agreement and after some differences after the foundation of a Kurdish Government in Iraqi Kurdistan in 1992 he later had a better relationship.[52]

In the early 1990s, interviews given to both Doğu Perinçek and Hasan Bildirici he mentioned his willingness to achieve a peaceful solution to the conflict.[54] In another given to Oral Çalışlar, he emphasized the difference between independence and separatism. He articulated the view that different nations were able to live in independence within the same state if they had equal rights.[55] Then in 1993, upon request of Turkish president Turgut Özal, Öcalan met with Jalal Talabani for negotiations following which Öcalan declared a unilateral cease fire which had a duration from 20 March to 15 April.[56][57] Later he prolonged it in order to enable negotiations with the Turkish government. Soon after Özal died on 17 April 1993,[58] the initiative was halted by Turkey on the grounds that Turkey did not negotiate with terrorists.[56] During an International Kurdish Conference in Brussels in March 1994, his initiative for equal rights for Kurds and Turks within Turkey was discussed.[59] It is reported by Gottfried Stein, that at least during the first half of the 1990s, he used to live mainly in a protected neighborhood in Damascus.[59] On 7 May 1996, in the midst of another unilateral cease-fire declared by the PKK, an attempt to assassinate him in a house in Damascus, was unsuccessful.[60][61]

Following the protests which arose against the prohibition of the PKK in Germany, Öcalan had several meetings with politicians from Germany who came to hold talks with him.[62] In the summer of 1995 the president of the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution (Verfassungsschutz) Klaus Grünewald came to visit him,[62][63] And with the German MP Heinrich Lummer of the Christian Democratic Union of Germany (CDU) he held meetings in October 1995 in Damascus and March 1996, during which they discussed the PKK's activities in Germany.[62] Öcalan assured him that the PKK would support a peaceful solution for the conflict. Back in Germany, Lummer made a statement in support for further negotiations with Öcalan.[64] With time, the United States (1997),[65] European Union, Syria, Turkey, and other countries have included the PKK on their lists of terrorist organizations.[66][67] A Greek parliamentary delegation from the PASOK came to visit him in the Beqaa valley on 17 October 1996.[62] During his stay in Syria he has published several books concerning the Kurdish revolution.[59] On at least one occasion, in 1993, he was detained and held by Syria's General Intelligence Directorate, but later released.[68] Until 1998, Öcalan was based in Syria. As the situation deteriorated in Turkey, the Turkish government openly threatened Syria over its support for the PKK.[69] As a result, the Syrian government forced Öcalan to leave the country but still refused turning him over to the Turkish authorities. In October 1998, Öcalan prepared for his departure from Syria and during a meeting in Kobane, he unsuccessfully attempted to lay the foundations for a new party which failed due to Syrian intelligence's obstruction.[70]

Exile in Europe

Öcalan left Syria on 9 October 1998 and for the next four months, he toured several European countries advocating for a solution of the Kurdish-Turkish conflict.[71] Öcalan first went to Russia where the Russian parliament voted on 4 November 1998 to grant him asylum.[72] On 6 November 109 Greek parliamentarians invited Öcalan to stay in Greece, a move which was repeated by Panayioitis Sgouridis,[72] the deputy speaker of the Greek Parliament at the time.[73] Öcalan then chose to travel to Italy, where he landed on 12 November 1998 at the airport in Rome.[74]

In 1998 the Turkish government requested the extradition of Öcalan from Italy,[75] where he applied for political asylum upon his arrival. He was detained by the Italian authorities due to an arrest warrant issued by Germany.[76] But Italy did not extradite him to Germany, who refused to hold a trial on Öcalan in its country.[77] The German chancellor Gerhard Schröder as well as the Minister of the Interior Otto Schily preferred that Öcalan would be tried by an unspecified "European Court".[74] Italy also didn't extradite him to Turkey.[76] The Italian prime minister Massimo D'Alema announced it was contrary to Italian law to extradite someone to a country where the defendant is threatened with a capital punishment.[78] But Italy also didn't want Öcalan to stay, and pulled several diplomatic strings to compel him to leave the country,[71] which was accomplished on 16 January[79] when he departed to Nizhny Novgorod in hope to find a safe haven in Russia.[71] But in Russia he was not as much welcomed as in October, and he had to wait for a week at the airport of Strigino International Airport in Nizhny Novgorod.[71] From Russia, he took an airplane from Saint Petersburg to Greece where he arrived in Athens upon the invitation of Nikolas Naxakis, a retired Admiral on 29 January 1999.[71] He spent the night as a guest of the popular Greek author Voula Damianakou in Nea Makri.[71]

Following this, Öcalan attempted to travel to The Hague, to pursue a settlement of his legal situation at the International Criminal Court, but the Netherlands would not let his plane land and sent him back to Greece where he landed on the island Corfu in the Ionean Sea.[71] Öcalan then decided to fly to Nairobi at the invitation of Greek diplomats.[80] At that time he was defended by Britta Böhler, a high-profile German attorney who argued that the crimes he was accused of would have to be proven in court and attempted to reach that the International Court in The Hague would assume the case.[81]

Abduction, trial, and imprisonment

Öcalan was abducted in Kenya on 15 February 1999, while on his way from the Greek embassy to Jomo Kenyatta International Airport in Nairobi, in an operation by the Turkish National Intelligence Organization (Turkish: Millî İstihbarat Teşkilatı , MIT) with the help of the CIA.[82] According to the Turkish newspaper Vatan, the Americans transferred him to the Turkish authorities, who flew him back to Turkey for trial.[83]

Following his capture, the Greek Government was in turmoil and Foreign Minister Theodoros Pangalos, Interior Minister Alekos Papadopoulos and the Minister of Public Order Philipos Petsalnikos resigned from their posts.[84] Costoulas, the Greek ambassador who protected him, said that his own life was in danger after the operation.[85] According to Nucan Derya, Öcalan's interpreter in Kenya, the Kenyans had warned the Greek ambassador that "something" might happen if he didn't leave four days prior and that they were given the assurance by Pangalos that Öcalan would have safe passage to Europe. Öcalan was determined to travel to Amsterdam and face the accusations of terrorism.[86] Öcalan's capture led thousands of Kurds to hold worldwide protests condemning his capture at Greek and Israeli embassies. Kurds living in Germany were threatened with deportation if they continued to hold demonstrations in support of Öcalan. The warning came after three Kurds were killed and 16 injured during the 1999 attack on the Israeli consulate in Berlin.[87][88] A group named the Revenge Hawks of Apo set fire to a department store in Kadiköy Istanbul, causing the death of 13 people.[89] In several European capitals and larger cities[90] as well as in Iraq, Iran and also Turkey protests were organized against his capture.[91]

Trial

He was brought to İmralı island, where he was interrogated for a period of 10 days without being allowed to see or speak to his lawyers.[92] A state security court consisting of one military and two civilian judges was established on İmralı island to try Öcalan.[93] A delegation of three Dutch lawyers who intended to defend him were not allowed to meet with their client and detained for questioning at the airport on the grounds that they acted as "PKK militants" and not lawyers; they were sent back to the Netherlands.[80] On the seventh day a judge took part in the interrogations, and prepared a transcript of it.[92][94] The trial began on 31 May 1999 on the İmralı island[95] in the Sea of Marmara, and was organized by the Ankara State Security Court.[96] During the trial, he was represented by the Asrın Law Office.[97] His lawyers had difficulty in representing him adequately as they were allowed only two interviews per week of initially a duration of 20 minutes, and later 1 hour, of which several were cancelled due to "bad weather" or because the authorities didn't give the permission needed for them.[92] Also his lawyers were unaware of what the charges might be, and received the formal indictment only after excerpts of it were already presented to the press.[94] The trial was accompanied by arrests of scores of Kurdish politicians from the People's Democracy Party (HADEP).[98] In mid-June 1999, the Grand National Assembly of Turkey approved the removal of military judges from the State Security Courts, in an attempt to address criticism from the European Court of Human Rights[99] and a civilian judge assumed the post of the military judge.[93] Shortly before the verdict was read out by Judge Turgut Okyay, when asked about his final remarks, he again offered to play a role in the peace finding process.[100] Öcalan was charged with treason and separatism and sentenced to death on 29 June 1999.[101] He was also banned from holding public office for life.[102]

On the same day, Amnesty International (AI) demanded a re-trial[94] and Human Rights Watch (HRW) questioned the fact that witnesses brought by the defense were not heard in the trial.[101] In 1999 the Turkish Parliament discussed a so-called Repentance Bill which would commute Öcalans death sentence to 20 years imprisonment and allow PKK militants to surrender with a limited amnesty, but it didn't pass due to resistance from the far-right around the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP).[103] In January 2000 the Turkish government declared the death sentence was delayed until the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) reviewed the verdict.[104] Upon the abolition of the death penalty in Turkey in August 2002,[105] in October of that year, the security court commuted his sentence to life imprisonment.[106]

In an attempt to reach a verdict which was more favorable to Öcalan, he appealed at the ECHR at Strasbourg, which accepted the case in June 2004.[107] In 2005, the ECHR ruled that Turkey had violated articles 3, 5, and 6 of the European Convention of Human Rights by refusing to allow Öcalan to appeal his arrest and by sentencing him to death without a fair trial.[108] Öcalan's request for a retrial was refused by Turkish courts.[109]

Detention conditions

After his capture, Öcalan was held in solitary confinement as the only prisoner on İmralı island in the Sea of Marmara. Following the commutation of the death sentence to a life sentence in 2002,[110] Öcalan remained imprisoned on İmralı, and was the sole inmate there. Although former prisoners at İmralı were transferred to other prisons, more than 1,000 Turkish military personnel were stationed on the island to guard him. In November 2009, Turkish authorities announced that they were ending his solitary confinement by transferring several other prisoners to İmralı.[111] They said that Öcalan would be allowed to see them for ten hours a week. The new prison was built after the Council of Europe's Committee for the Prevention of Torture visited the island and objected to the conditions in which he was being held.[112][113] From 27 July 2011 until 2 May 2019 his lawyers have not been allowed to see Abdullah Öcalan.[114] From July 2011 until December 2017 his lawyers filed more than 700 appeals for visits, but all were rejected.[115]

There have been held regular demonstrations by the Kurdish community to raise awareness of the isolation of Öcalan.[116] In October 2012 several hundred Kurdish political prisoners went on hunger strike for better detention conditions for Öcalan and the right to use the Kurdish language in education and jurisprudence. The hunger strike lasted 68 days until Öcalan demanded its end.[117] Öcalan was banned from receiving visits almost two years from 6 October 2014 until 11 September 2016, when his brother Mehmet Öcalan visited him for Eid al-Adha.[118] In 2014 the ECHR ruled in that there was a violation of article 3 in regards of him being to only prisoner on İmarli island until 17 November 2009, as well as the impossibility to appeal his verdict.[119] On 6 September 2018 visits from lawyers were banned for six months due to former punishments he received in the years 2005–2009, the fact that the lawyers made their conversations with Ocalan public, and the impression that Öcalan was leading the PKK through communications with his lawyers.[114] He was again banned from receiving visits until 12 January 2019 when his brother was permitted to visit him a second time. His brother said his health was good.[120] The ban on the visitation of his lawyers was lifted in April 2019, and Öcalan saw his lawyers on 2 May 2019.[114]

Legal prosecution of sympathizers of Abdullah Öcalan

In 2008, the Justice Minister of Turkey, Mehmet Ali Şahin, said that between 2006 and 2007, 949 people were convicted and more than 7,000 people prosecuted for calling Öcalan "esteemed" (Sayın).[121]

The Kurdish people

Involvement in peace initiatives

| Part of a series on the Kurdish–Turkish conflict |

| Kurdish–Turkish peace process |

|---|

|

In November 1998, Öcalan elaborated on a 7-point peace plan according to which the Turkish attacks on Kurdish villages should stop, the refugees would be allowed to return, the Kurdish people would be granted autonomy within Turkey, the Kurds would receive the equal democratic rights as the Turks and the Turkish government supported village guards system shall come to an end and the Kurdish language and culture was to be officially recognized.[122] In January 1999 during his stay in Europe, Öcalan saw the parties liberation struggle focus to have developed from guerrilla warfare to dialogue and negotiations.[123] After his capture Öcalan called for a halt in PKK attacks, and advocated for a peaceful solution for the Kurdish conflict inside the borders of Turkey.[124][125][126][page needed] In October 1999, eight PKK militants around the former European PKK spokesman Ali Sapan turned themselves in to Turkey on request of Öcalan.[127] Depending on their treatment, the other PKK militants would turn themselves in as well, his attorney announced.[127] But the eight, as well as another group which surrendered a few weeks later in Istanbul, were imprisoned and the peace initiative was dismissed by the Turkish Government.[128] Öcalan called for the foundation of a "Truth and Justice Commission" by Kurdish institutions in order to investigate war crimes committed by both the PKK and Turkish security forces. A similar structure began functioning in May 2006.[129] In March 2005, Öcalan issued the Declaration of Democratic confederalism in Kurdistan[130] calling for a border-free confederation between the Kurdish regions of Southeastern Turkey (called "Northern Kurdistan" by Kurds[131]), Northeast Syria ("Western Kurdistan"), Northern Iraq ("South Kurdistan"), and Northwestern Iran ("East Kurdistan"). In this zone, three bodies of law would be implemented: EU law, Turkish/Syrian/Iraqi/Iranian law and Kurdish law. This proposal was adopted by the PKK programme following the "Refoundation Congress" in April 2005.[132]

Öcalan had his lawyer Ibrahim Bilmez[133] release a statement on 28 September 2006 calling on the PKK to declare a ceasefire and seek peace with Turkey. Öcalan's statement said, "The PKK should not use weapons unless it is attacked with the aim of annihilation," and "it is very important to build a democratic union between Turks and Kurds. With this process, the way to democratic dialogue will be also opened".[134] He worked on a solution for the Kurdish–Turkish conflict, which would include a decentralization and democratization of Turkey within the frame of the European Charter of local Self-Government, which was also signed by Turkey, but his 160-page proposal on the subject was confiscated by the Turkish authorities in August 2009.[135]

On 31 May 2010, Öcalan said he was abandoning the ongoing dialogue with Turkey, as "this process is no longer meaningful or useful". Öcalan stated that Turkey had ignored his three protocols for negotiation: (a) his terms of health and security, (b) his release, and (c) a peaceful resolution to the Kurdish issue in Turkey. Though the Turkish government had received Öcalan's protocols, they were never released to the public. Öcalan said he would leave the top PKK commanders in charge of the conflict, but that this should not be misinterpreted as a call for the PKK to intensify its armed conflict with Turkey.[136][137]

In January 2013, peace negotiations between the PKK and the Turkish Government were initiated and from between January[138] and March he met several times with politicians of Peace and Democracy Party (BDP) on Imralı Island.[139] On 21 March, Öcalan declared a ceasefire between the PKK and the Turkish state. Öcalan's statement was read to hundreds of thousands of Kurds in Diyarbakır who had gathered to celebrate the Kurdish New Year (Newroz). The statement said in part, "Let guns be silenced and politics dominate... a new door is being opened from the process of armed conflict to democratization and democratic politics. It's not the end. It's the start of a new era."[140] Soon after Öcalan's declaration, the functional head of the PKK, Murat Karayılan responded by promising to implement a ceasefire.[141] During the peace process, the pro-Kurdish Peoples' Democratic Party (HDP) entered parliament during the parliamentarian election of June 2015.[142] The ceasefire ended after in July 2015 two Turkish police officers were killed in Ceylanpinar.[143]

Political ideological shift

Since his incarceration, Öcalan has significantly changed his ideology through exposure to Western social theorists such as Murray Bookchin, Immanuel Wallerstein and Hannah Arendt.[27] Abandoning his old Marxism-Leninist[27] and Stalinist beliefs,[124][144][145] Öcalan fashioned his ideal society called democratic confederalism.[145][27] In early 2004, Öcalan attempted to arrange a meeting with Murray Bookchin through Öcalan's lawyers, describing himself as Bookchin's "student" eager to adapt Bookchin's thought to Middle Eastern society. Bookchin was too ill to meet with Öcalan.[145]

Democratic confederalism

Democratic confederalism is a "system of popularly elected administrative councils, allowing local communities to exercise autonomous control over their assets, while linking to other communities via a network of confederal councils."[146] Decisions are made by communes in each neighborhood, village, or city. All are welcome to partake in the communal councils, but political participation is not mandated. There is no private property, but rather "ownership by use, which grants individuals usage rights to the buildings, land, and infrastructure, but not the right to sell and buy on the market or convert them to private enterprises".[146] The economy is in the hands of the communal councils, and is thus (in the words of Bookchin) 'neither collectivised nor privatised - it is common.'[146] Feminism, ecology, and direct democracy are essential in democratic confederalism.[147]

With his 2005 "Declaration of Democratic Confederalism in Kurdistan", Öcalan advocated for a Kurdish implementation of Bookchin's The Ecology of Freedom via municipal assemblies as a democratic confederation of Kurdish communities beyond the state borders of Syria, Iran, Iraq, and Turkey. Öcalan promoted a platform of shared values: environmentalism, self-defense, gender equality, and a pluralistic tolerance for religion, politics, and culture. While some of his followers questioned Öcalan's conversion from Marxism-Leninism to social ecology, the PKK adopted Öcalan's proposal and began to form assemblies.[124] It became also the ideology of the Democratic Union Party (PYD) and is applied in the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES).[27]

On women's rights

Öcalan is a supporter of the liberation of the women, he writes in his Freedom Manifesto for Women that all slavery is based on the housewifization of women.[148] He deems the woman often as being trapped in a situation where she accepts traditional gender roles and a disadvantaged relationship with a man.[148]

Personal life

According to his own account, while his father is Kurdish, his mother is Turkmen.[149] According to some sources, Öcalan's grandmother was an ethnic Turk.[150][151] Öcalan's mother, Esma Öcalan (Uveys)[152] was rather dominant and criticised his father, blaming him for their dire economic situation. He later explained in an interview that it was in his childhood he learned to defend himself from injustice.[153] Like many Kurds in Turkey, Öcalan was raised speaking Turkish; according to Amikam Nachmani, lecturer at the Bar-Ilan University in Israel, Öcalan did not know Kurdish when he met him in 1991. Nachmani: "He [Öcalan] told me that he speaks Turkish, gives orders in Turkish, and thinks in Turkish."[154] In 1978 Öcalan married Kesire Yildirim, who he had met at the Ankara University[155] and was of a better household than the regular revolutionaries around Öcalan.[156] They had a difficult marriage with reportedly many disputes and discussions.[157] In 1988, while representing the PKK in Athens, Greece, his wife unsuccessfully attempted to overthrow Öcalan, following which Yildirim went underground.[156]

After his sister Havva was married to a man from another village in an arranged marriage, he felt regret. This event led Öcalan to his policies towards the liberation of women from the traditional suppressed female role.[153] Öcalan's brother Osman became a PKK commander until he defected from the PKK with several others to establish the Patriotic and Democratic Party of Kurdistan.[158] His other brother, Mehmet Öcalan, is a member of the pro-Kurdish Peace and Democracy Party (BDP).[159] Fatma Öcalan is the sister of Abdullah Öcalan[160] and Dilek Öcalan, a former parliamentarian of the HDP, is his niece.[161] Ömer Öcalan, a current member of parliament for the HDP, is his nephew.[162][163]

Honorary citizenships

Several localities have awarded him with an honorary citizenship:

Publications

Öcalan is the author of more than 40 books, four of which were written in prison. Many of the notes taken from his weekly meetings with his lawyers have been edited and published. He has also written articles for the newspaper Özgür Gündem which is a newspaper that reported on the Kurdish-Turkish conflict, under the pseudonym of Ali Firat.[170]

Books

- Interviews and Speeches. London: Kurdistan Solidarity Committee; Kurdistan Information Centre, 1991. 46 p.

- "Translation of his 1999 defense in court". Archived from the original on 20 October 2007. Retrieved 24 April 2007.

- Prison Writings: The Roots of Civilisation. London; Ann Arbor, MI: Pluto, 2007. ISBN 978-0-7453-2616-0.

- Prison Writings Volume II: The PKK and the Kurdish Question in the 21st Century. London: Transmedia, 2011. ISBN 978-0-9567514-0-9.

- Democratic Confederalism. London: Transmedia, 2011. ISBN 978-3-941012-47-9.

- Prison Writings III: The Road Map to Negotiations. Cologne: International Initiative, 2012. ISBN 978-3-941012-43-1.

- Liberating life: Women's Revolution. Cologne, Germany: International Initiative Edition, 2013. ISBN 978-3-941012-82-0.

- Manifesto for a Democratic Civilization, Volume 1. Porsgrunn, Norway: New Compass, 2015. ISBN 978-82-93064-42-8.

- Defending a Civilisation.[when?]

- The Political Thought of Abdullah Öcalan. London: Pluto Press, 2017. ISBN 978-0-7453-9976-8.

- Manifesto for a Democratic Civilization, Volume 2. Porsgrunn, Norway: New Compass, 2017. ISBN 978-82-93064-48-0

See also

References

- ^ a b "International Initiative: Celebrate Öcalan's birthday with us". ANFNews. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ^ Türkmen, Gülay (2020). "Religion in Turkey's Kurdish Conflict". In Djupe, Paul A.; Rozell, Mark J.; Jelen, Ted G. (eds.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Politics and Religion. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780190614379.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-061438-6.

- ^ "Profile: Abdullah Ocalan ( Greyer and tempered by long isolation, PKK leader is braving the scepticism of many Turks, and some of his own fighters)". Al Jazeera. 21 March 2013. Retrieved 30 October 2024.

- ^ Özcan, Ali Kemal. Turkey's Kurds: A Theoretical Analysis of the PKK and Abdullah Öcalan. London: Routledge, 2005.

- ^ Phillips, David L. (2017). The Kurdish Spring: A New Map of the Middle East. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-48036-9.

- ^ Butler, Daren (21 March 2013). "Kurdish rebel chief Ocalan dons mantle of peacemaker". UK Reuters. Archived from the original on 14 July 2018.

- ^ Öcalan, Abdullah (2015). Capitalism: The Age of Unmasked Gods and Naked Kings. New Compass. p. 115.

- ^ Paul J. White, Primitive rebels or revolutionary modernizers?: The Kurdish national movement in Turkey, Zed Books, 2000, "Professor Robert Olson, University of Kentucky"

- ^ a b Political Violence against Americans 1999. Bureau of Diplomatic Security. 2000. p. 123. ISBN 978-1-4289-6562-1.

- ^ "Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- ^ Mango, Andrew (2005). Turkey and the War on Terror: 'For Forty Years We Fought Alone'. Routledge: London. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-203-68718-5.

The most ruthless among them was Abdullah Öcalan, known as Apo (a diminutive for Abdullah; the word also means 'uncle' in Kurdish).

- ^ Jongerden, Joost (2007). The Settlement Issue in Turkey and the Kurds: An Analysis of Spatial Policies, Modernity and War. Leiden, the Netherlands: Brill. p. 57. ISBN 978-90-04-15557-2.

In 1975 the group settled on a name, the Kurdistan Revolutionaries (Kurdistan Devrimcileri), but others knew them as Apocu, followers of Apo, the nickname of Abdullah Öcalan (apo is also Kurdish for uncle).

- ^ Powell, Colin (5 October 2001). "2001 Report on Foreign Terrorist Organizations". Foreign Terrorist Organizations. Washington, DC: Bureau of Public Affairs, U.S. State Department. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ^ "AMs criticise Kurdish leader's treatment". BBC News. 20 March 2019. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ "Jailed PKK leader Abdullah Ocalan granted rare family visit". Rudaw. 3 March 2020. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ^ Weiner, Tim (20 February 1999). "U.S. Helped Turkey Find and Capture Kurd Rebel (Published 1999)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- ^ "Öcalan v Turkey (App no 46221/99) ECHR 12 May 2005 | Human Rights and Drugs". www.hr-dp.org. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- ^ "Prison island trial for Ocalan". BBC News. 24 March 1999.

- ^ Marlies Casier, Joost Jongerden, Nationalisms and Politics in Turkey: Political Islam, Kemalism and the Kurdish Issue, Taylor & Francis, 2010, p. 146.

- ^ Parliamentary Assembly Documents 1999 Ordinary Session (fourth part, September 1999), Volume VII. Council of Europe. 1999. p. 18. ISBN 978-92-871-4139-2 – via books.google.com.

- ^ Özcan, Ali Kemal (2006). Turkey's Kurds: A Theoretical Analysis of the PKK and Abdullah Ocalan. Routledge. p. 205. ISBN 978-0-415-36687-8.

- ^ Mag. Katharina Kirchmayer, The Case of the Isolation Regime of Abdullah Öcalan: A Violation of European Human Rights Law and Standards?, GRIN Verlag, 2010, p. 37

- ^ "Jailed PKK leader visit ban lifted, Turkish minister says". Reuters. 16 May 2019.

- ^ "What kind of peace? The case of the Turkish and Kurdish peace process". openDemocracy. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- ^ Argentieri, Benedetta (3 February 2015). "One group battling Islamic State has a secret weapon – female fighters". Reuters. Archived from the original on 22 August 2019. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- ^ Lau, Anna; Baran, Erdelan; Sirinathsingh, Melanie (18 November 2016). "A Kurdish response to climate change". openDemocracy. Archived from the original on 12 November 2017. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Novellis, Andrea. "The Rise of Feminism in the PKK: Ideology or Strategy?" (PDF). Zanj: The Journal of Critical Global South Studies. 2: 116. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 July 2021.

- ^ "A Short Biography". Kurdistan Workers' Party. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ^ Kutschera, Chris (1999). "Abdullah Ocalan's Last Interview". Archived from the original on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- ^ Aliza Marcus, Blood and Belief, New York University Press, 2007. (p. 16) [ISBN missing]

- ^ Marcus, Aliza (2009). Blood and Belief: The PKK and the Kurdish Fight for Independence. NYU Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-8147-9587-3.

- ^ a b c d Marcus, Aliza (2009), pp. 17–18

- ^ a b c Brauns, Nikolaus; Kiechle, Brigitte (2010). PKK – Perspektiven des kurdischen Freiheitskampfes: zwischen Selbstbestimmung, EU und Islam (in German). Schmetterling-Verlag. p. 39. ISBN 978-3-89657-564-7.

- ^ Uğur Mumcu (Haziran 2020). Kürt Dosyası. SBF'de Şafak Bildirisi Dağıtılıyor. Uğur Mumcu Araştırmacı Gazetecilik Vakfı. p. 7. ISBN 9786054274512

- ^ Marcus, Aliza (2009) p. 23

- ^ Yılmaz, Kamil (2014). Disengaging from Terrorism – Lessons from the Turkish Penitents. Routledge. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-317-96449-0.

- ^ Koru, Fehmi (8 June 1999). "Too many questions, but not enough answers". Turkish Daily News. Archived from the original on 13 February 2009. Retrieved 22 December 2008.

- ^ Nevzat Cicek (31 July 2008). "'Pilot Necati' sivil istihbaratçıymış". Taraf (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 9 August 2008. Retrieved 4 January 2009.

Abdullah Öcalan'ın İstanbul'dan Ankara'ya gelmesine keşke izin verilmeseydi. O zamanlar Dev-Genç'i bölmek için böyle bir yol izlendi... Kürt gençlerini Marksistler'in elinden kurtarmak ve Dev-Genç'in bölünmesi hedeflendi. Bunda başarılı olundu olunmasına ama Abdullah Öcalan yağdan kıl çeker gibi kaydı gitti. Keşke Tuzluçayır'da öldürülseydi!

- ^ "Ocalan Used Charisma, Guns, Bombs". AP News. Retrieved 14 May 2021.

- ^ "Who is who in Turkish politics" (PDF). Heinrich Böll Stiftung. pp. 11–13. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 November 2019. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- ^ a b Jongerden, Joost; Akkaya, Ahmet Hamdi (1 June 2012). "The Kurdistan Workers Party and a New Left in Turkey: Analysis of the revolutionary movement in Turkey through the PKK's memorial text on Haki Karer". European Journal of Turkish Studies. Social Sciences on Contemporary Turkey (14). doi:10.4000/ejts.4613. hdl:1854/LU-3101207. ISSN 1773-0546. Archived from the original on 16 February 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- ^ Jongerden, Joost; Akkaya, Ahmet Hamdi (1 June 2012). "The Kurdistan Workers Party and a New Left in Turkey: Analysis of the revolutionary movement in Turkey through the PKK's memorial text on Haki Karer". European Journal of Turkish Studies. Social Sciences on Contemporary Turkey (14). doi:10.4000/ejts.4613. hdl:1854/LU-3101207. ISSN 1773-0546. Archived from the original on 16 February 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- ^ a b Stein, Gottfried (1994). Endkampf um Kurdistan?: die PKK, die Türkei und Deutschland (in German). Aktuell. p. 67. ISBN 3-87959-510-0.

- ^ a b c Yilmaz, Özcan (2015). La formation de la nation kurde en Turquie (in French). Graduate Institute Publications. p. 137. ISBN 978-2-940503-17-9.

- ^ "Kurdish leader Ocalan apologizes during trial". CNN. 31 May 1999. Archived from the original on 9 December 2001. Retrieved 11 January 2008.

- ^ Andrew Mango (2005). Turkey and the War on Terror: For Forty Years We Fought Alone (Contemporary Security Studies). Routledge. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-415-35002-0. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ^ a b c Özcan, Ali Kemal (2005). Turkey's Kurds: A Theoretical Analysis of the PKK and Abdullah Ocalan (PDF). Routledge. p. 104.

- ^ Özcan, Ali Kemal (2005) p. 105

- ^ "Letter to Italian Prime Minister Massimo D'Alema". Human Rights Watch. 21 November 1998.

- ^ "Turkey: No security without human rights". Amnesty International. October 1996. Archived 5 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ulkumen Rodophu; Jeffrey Arnold; Gurkan Ersoy (6 February 2004). "Special Report: Terrorism in Turkey" (PDF). Archived 28 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Kutschera, Chris (15 July 1994). "Mad Dreams of Independence". MERIP. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- ^ Cigerli, Sabri; Saout, Didier Le (2005). Ocalan et le PKK: Les mutations de la question kurde en Turquie et au moyen-orient (in French). Maisonneuve et Larose. p. 173. ISBN 978-2-7068-1885-1.

- ^ Gunes, Cengiz (2013). The Kurdish National Movement in Turkey: From Protest to Resistance. Routledge. p. 127. ISBN 978-1-136-58798-6.

- ^ Gunes, Cengiz (2013), pp. 127–128

- ^ a b Nahost Jahrbuch 1993: Politik, Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft in Nordafrika und dem Nahen und Mittleren Osten (in German). Springer-Verlag. 2013. p. 21. ISBN 978-3-322-95968-3.

- ^ White, Paul J. (2000). "Appendix 2". Primitive Rebels Or Revolutionary Modernizers?: The Kurdish National Movement in Turkey. London: Zed Books. pp. 223–. ISBN 978-1-85649-822-7. OCLC 1048960654.

- ^ "Obituary: Turgut Ozal". The Independent. 19 April 1993. Archived from the original on 6 May 2022. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- ^ a b c Stein, Gottfried (1994), p. 69

- ^ Gunes, Cengiz (2013), p. 134

- ^ "Confessions of a former Turkish National Intelligence official". Medya News. 5 November 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d Cigerli, Sabri; Saout, Didier Le (2005). Öcalan et le PKK: Les mutations de la question kurde en Turquie et au moyen-orient (in French). Maisonneuve et Larose. p. 222. ISBN 978-2-7068-1885-1.

- ^ "Kurden : Tips vom PKK-Chef – Der Spiegel". www.spiegel.de. December 1995. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ^ Özcan, Ali Kemal (2006), p. 206

- ^ "Foreign Terrorist Organizations". U.S. Department of State. 28 September 2012.

- ^ "MFA – A Report on the PKK and Terrorism". Retrieved 23 January 2015.

- ^ "Turco-Syrian Treaty". 20 October 1998. Archived from the original on 9 February 2002. Retrieved 9 February 2002.

- ^ "(unknown original Turkish title)" [[PKK Leader Abdullah Ocalan Arrested in Syria]]. Günaydın (in Turkish). translated by Foreign Broadcast Information Service. 16 December 1993. p. 72. hdl:2027/uiug.30112106671198. FBIS-WEU-93-240.

- ^ G. Bacik; BB Coskun (2011). "The PKK problem: Explaining Turkey's failure to develop a political solution" (PDF). Studies in Conflict & Terrorism. 34 (3): 248–265. doi:10.1080/1057610X.2011.545938. ISSN 1057-610X. S2CID 109645456. Retrieved 13 July 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Ünver, H. Akın (2016). "Transnational Kurdish geopolitics in the age of shifting borders". Journal of International Affairs. 69 (2): 79–80. ISSN 0022-197X. JSTOR 26494339.

- ^ a b c d e f g "A Most Unwanted Man". Los Angeles Times. 19 February 1999. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ a b Radu, Michael (2005). Dilemmas of Democracy and Dictatorship: Place, Time and Ideology in Global Perspective. Transaction Publishers. p. 73. ISBN 978-1-4128-2171-1.

- ^ Varouhakis, Miron (2009). "Fiasco in Nairobi, Greek Intelligence and the Capture of PKK Leader Abdullah Ocalan in 1999" (PDF). Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). p. 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 May 2009. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ^ a b Traynor, Ian (28 November 1998). "Italy 'may expel Kurd leader'". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ Italian diplomacy tries to free herself from the tangle in which it is located, between Turks and Kurds, " internationalizing " the crisis:Buonomo, Giampiero (2000). "Ocalan: la suggestiva strategia turca per legittimare la pena capitale". Diritto&Giustizia Edizione Online. Archived from the original on 24 March 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- ^ a b Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "Refworld | Amnesty International Report 1999 – Italy". Refworld. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- ^ Gökkaya, Hasan (15 February 2019). "Der mächtigste Häftling der Türkei". Die Zeit. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- ^ Stanley, Alessandra (21 November 1998). "Italy Rejects Turkey's Bid For the Extradition of Kurd". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- ^ Gunter, Michael M. (2000). "The Continuing Kurdish Problem in Turkey after Öcalan's Capture". Third World Quarterly. 21 (5): 850. doi:10.1080/713701074. ISSN 0143-6597. JSTOR 3993622. S2CID 154977403.

- ^ a b Zaman, Amberin (18 February 1999). "Washingtonpost.com: Turkey Celebrates Capture of Ocalan". www.washingtonpost.com. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- ^ "Von der RAF-Sympathisantin zur Anwältin Öcalans". Die Welt. 3 February 1999. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- ^ Weiner, Tim (20 February 1999). "U.S. Helped Turkey Find and Capture Kurd Rebel". The New York Times.

- ^ "Öcalan bağımsız devlete engeldi". Vatan (in Turkish). 15 October 2008. Archived from the original on 18 October 2008. Retrieved 15 October 2008.

Öcalan yakalandığında ABD, bağımsız bir devlet kurma isteğindeydi. Öcalan, konumu itibariyle, araç olma işlevi bakımından buna engel bir isimdi. ABD bölgede yeni bir Kürt devleti kurabilmek için Öcalan'ı Türkiye'ye teslim etti.

- ^ Murphy, Brian (18 February 1999). "Three Greek Cabinet Ministers Resign Over Ocalan Affair". www.washingtonpost.com. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ Ünlü, Ferhat (17 July 2007). "Türkiye Öcalan için Kenya'ya para verdi". Sabah (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 12 January 2008. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- ^ "Ocalan interpreter tells how trap was set". The Irish Times. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ "Kurds seize embassies, wage violent protests across Europe". CNN. 17 February 1999.

- ^ Yannis Kontos, "Kurd Akar Sehard Azir, 33, sets himself on fire during a demonstration outside the Greek Parliament in Central Athens, Greece, on Monday, 15 February 1999" Archived 19 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Photostory, July 1999

- ^ Shatzmiller, Maya (2005). Nationalism and Minority Identities in Islamic Societies. McGill-Queen's Press – MQUP. p. 249. ISBN 978-0-7735-2847-5.

- ^ Gunter, Michael M. (2000), p. 851

- ^ van Bruinessen, Martin; Bouyssou, Rachel (1999). "Öcalan capturé : et après? Une question kurde plus épineuse que jamais". Critique Internationale (4). Sciences Po University Press: 39–40. doi:10.3917/crii.p1999.4n1.0039. ISSN 1290-7839. JSTOR 24563462.

- ^ a b c d e "University of Minnesota Human Rights Library". hrlibrary.umn.edu. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- ^ a b Chiapetta, Hans (April 2001). "Rome, 11/15/1998: Extradition or Political Asylum for the Kurdistan Workers Party's Leader Abdullah Ocalan?" (PDF). Pace International Law Review. 13: 145. doi:10.58948/2331-3536.1206. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 April 2019.

- ^ a b c "Amnesty International calls for a retrial of PKK leader Abdullah Öcalan" (PDF). Amnesty International. 29 June 1999. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 April 2021. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- ^ "Trial Of Abdullah Ocalan". The Irish Times. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ "Human Rights Watch: Ocalan Trial Monitor". www.hrw.org. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- ^ Fisher, Tony (30 October 2018). "Turkey Report, Trial of Kurdish Lawyers" (PDF). eldh.eu. European Association of Lawyers for Democracy & World Human Rights. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 December 2020. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- ^ Laizer, Sheri (1999). "Abdullah Ocalan: A plea for justice". Socialist Lawyer (31): 6–8. ISSN 0954-3635. JSTOR 42949064.

- ^ Morris, Chris (18 June 1999). "Military judge barred from Ocalan trial". news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

- ^ agencies, Guardian staff and (29 June 1999). "Ocalan sentenced to death". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- ^ a b Hacaoglu, Selcan (29 June 1999). "The Argus-Press". Retrieved 24 May 2016 – via Google News Archive Search.

- ^ "Text of the Ocalan verdict". BBC News. 29 June 1999.

- ^ "Bill to spare life of Ocalan withdrawn by Ecevit". The Irish Times. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- ^ "Turkey delays execution of Kurdish rebel leader Ocalan". CNN. 12 January 2000. Archived from the original on 26 May 2006.

- ^ "Turkey abolishes death penalty". The Independent. 3 August 2002. Archived from the original on 23 February 2019.

- ^ Luban, David (2014). International and Transnational Criminal Law. Wolters Kluwer Law & Business. ISBN 978-1-4548-4850-9.

- ^ "29. Juni 2004 – Vor 5 Jahren: Abdullah Öcalan wird zum Tod verurteilt". WDR (in German). 29 June 2004. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- ^ "HUDOC Search Page". cmiskp.echr.coe.int. Retrieved 23 January 2015.

- ^ "There will absolutely be no retrial for Abdullah Öcalan". Daily Sabah. 29 March 2013. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- ^ "Kurd's Death Sentence Commuted to Life Term". Los Angeles Times. 4 October 2002. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- ^ "PKK leader Ocalan gets company in prison". United Press International. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- ^ Villelabeitia, Ibon (18 November 2009). "Company at last for Kurdish inmate alone for ten years". The Scotsman. Archived from the original on 13 August 2011. Retrieved 27 November 2009.

- ^ Erduran, Esra (10 November 2009). "Turkey building new prison for PKK members". Southeast European Times. Archived from the original on 19 November 2009. Retrieved 27 November 2009.

- ^ a b c "Öcalan-Anwälte: Kontaktverbot faktisch in Kraft". ANF News (in German). Archived from the original on 17 May 2019. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- ^ "Lawyers' appeal to visit Öcalan rejected for the 710th time". Firat News Agency. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 17 February 2018.

- ^ "Demonstrations for Öcalan in Europe". ANF News. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 27 December 2018.

- ^ White, Paul (2015). The PKK. London: Zed Books. p. 88. ISBN 978-1-78360-037-3.

- ^ "Inhaftierter PKK-Chef: Erstmals seit zwei Jahren Familienbesuch für Öcalan". Der Spiegel. 12 September 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ^ "Terrorism and the European Convention on Human Rights" (PDF). European Court of Human Rights. 18 March 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 July 2013.

- ^ "PKK's Ocalan visited by family in Turkish prison, first time in years". Kurdistan24. Archived from the original on 30 August 2019. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ^ Gunes, Cengiz; Zeydanlioglu, Welat (2013). The Kurdish Question in Turkey: New Perspectives on Violence, Representation, and Reconciliation. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-14063-2.

- ^ Abdullah Öcalan proposes 7-point peace plan Archived 6 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine Kurdistan Informatie Centrum Nederland

- ^ Interview with Abdullah Ocalan "Our First Priority Is Diplomacy" Archived 8 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine Middle East Insight magazine, January 1999

- ^ a b c Enzinna, Wes (24 November 2015). "A Dream of Secular Utopia in ISIS' Backyard". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- ^ Kurdistan Turkey: Abdullah Ocalan, The End of a Myth? The Middle East magazine, February 2000

- ^ van Bruinessen, Martin. Turkey, Europe and the Kurds after the capture of Abdullah Öcalan 1999

- ^ a b Zaman, Amberin (7 October 1999). "Kurds' Surrender Awakens Turkish Doves". Washington Post. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ Marcus, Aliza (2007). "Turkey's PKK: Rise, Fall, Rise Again?". World Policy Journal. 24 (1): 78. doi:10.1162/wopj.2007.24.1.75. ISSN 0740-2775. JSTOR 40210079.

- ^ Öldürülen imam ve 10 korucunun itibarı iade edildi Archived 8 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine, ANF News Agency, 30 May 2006.

- ^ "PKK ilk adına döndü". Hürriyet Daily News (in Turkish). 9 January 2009. Archived from the original on 11 February 2009. Retrieved 9 January 2009.

- ^ PKK Program (1995) Kurdish Library, 24 January 1995

- ^ PKK Yeniden İnşa Bildirgesi Archived 6 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine PKK web site, 20 April 2005

- ^ Kurdish leader calls for cease-fire Archived 24 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine NewsFlash

- ^ Kurdish rebel boss in truce plea, BBC News

- ^ Gunter, Michael (2014). Out of Nowhere: The Kurds of Syria in Peace and War. Oxford University Press. pp. 64–65. ISBN 978-1-84904-435-6.

- ^ "Turkey – PKK steps up attacks in Turkey". Retrieved 23 January 2015.

- ^ "Hürriyet – Haberler, Son Dakika Haberleri ve Güncel Haber". Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ "Kurdish Deputies Meet Ocalan on Imrali Island". Bianet – Bagimsiz Iletisim Agi. Retrieved 25 December 2020.

- ^ "Jailed Kurdish PKK rebel leader Ocalan expected to make ceasefire call". ekurd.net. Retrieved 25 December 2020.

- ^ "Inhaftierter Kurden-Chef stößt Tür zum Frieden auf". Reuters (in German). 21 March 2013. Archived from the original on 18 August 2019. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- ^ Welle (www.dw.com), Deutsche. "Hoffnung auf Frieden für die Kurden | DW | 23 March 2013". DW.COM (in German). Retrieved 25 December 2020.

- ^ Yildiz, Güney (8 June 2015). "Turkey's HDP challenges Erdogan and goes mainstream". BBC. Retrieved 25 December 2020.

- ^ "Acquittal of nine Ceylanpinar murder suspects upheld". IPA News. 16 April 2019. Retrieved 25 December 2020.

- ^ a b c Biehl, Janet (16 February 2012). "Bookchin, Öcalan, and the Dialectics of Democracy". New Compass. Archived from the original on 1 April 2016. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- ^ a b c Paul White, "Democratic Confederalism and the PKK's Feminist Transformation," in The PKK: Coming Down from the Mountains (London: Zed Books, 2015), pp. 126–149.

- ^ Öcalan, Abdullah (2011). Democratic Confederalism. London: Transmedia Publishing Ltd. p. 21. ISBN 978-3-941012-47-9.

- ^ a b Käser, Isabel (2021). The Kurdish Women's Freedom Movement. Cambridge University Press. p. 130. doi:10.1017/9781009022194.005. ISBN 978-1-316-51974-5. S2CID 242495844.

- ^ "Pişmanım, asmayın". www.hurriyet.com.tr (in Turkish). 23 February 1999. Retrieved 24 November 2020.

- ^ Blood and Belief: The Pkk and the Kurdish Fight for Independence, by Aliza Marcus, p. 15, 2007

- ^ Perceptions: journal of international affairs – Vol. 4, no. 1, SAM (Center), 1999, p. 142

- ^ Cigerli, Sabri; Saout, Didier Le (2005). Ocalan et le PKK: Les mutations de la question kurde en Turquie et au moyen-orient (in French). Maisonneuve et Larose. p. 187. ISBN 978-2-7068-1885-1.

- ^ a b Marcus, Aliza (2009). Blood and Belief: The PKK and the Kurdish Fight for Independence. NYU Press. pp. 16–17. ISBN 978-0-8147-9587-3.

- ^ Turkey: Facing a New Millennium: Coping With Intertwined Conflicts, Amikam Nachmani, p. 210, 2003

- ^ Marcus, Aliza (2012). Blood and Belief: The PKK and the Kurdish Fight for Independence. NYU Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-8147-5956-1.

- ^ a b Marcus, Aliza (2012) p. 43

- ^ Marcus, Aliza (2012). Blood and Belief: The PKK and the Kurdish Fight for Independence. NYU Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-8147-5956-1.

- ^ Kutschera, Chris (July 2005). "PKK dissidents accuse Abdullah Ocalan". The Middle East Magazine. Archived from the original on 7 February 2009. Retrieved 22 December 2008.

- ^ "BDP wants autonomy for Kurds in new Constitution", Hürriyet Daily News, 4 September 2011

- ^ "Travel ban for the sister and brother of Öcalan". ANF News. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- ^ "HDP MP Dilek Öcalan Sentenced to 2 Years, 6 Months in Prison". Bianet. 1 March 2018.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "HDP Urfa candidate, Öcalan: We are a house for all peoples". ANF News. Archived from the original on 1 March 2020. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ^ "Different identities enter Parliament with the HDP". ANF News. Archived from the original on 1 March 2020. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ^ a b c "'Öcalan factor' in the Italian debate". Ahval. Archived from the original on 22 October 2018. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ Zand, Bernhard; Höhler, Gerd (28 March 1999). "Spiegel-Gesspräch : 'Öcalan war eine heiße Kartoffel' – Der Spiegel 13/1999". Der Spiegel.

- ^ a b "Il Molise per il Kurdistan e per la pace: *Castelbottaccio e Castel del Giudice danno la cittadinanza onoraria ad Abdullah Öcalan" (in Italian). 2 May 2018. Retrieved 22 October 2018.

- ^ a b c "Martano: cittadinanza onoraria a Ocalan". Il Gallo (in German). 14 February 2017. Retrieved 22 October 2018.

- ^ Redazione. "Berceto (PR) Cittadinanza onoraria per Abdullah Öcalan". gazzettadellemilia.it (in Italian). Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- ^ "Protest gegen türkischen Druck auf italienische Stadtverwaltungen". ANF News (in German). Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- ^ Marcus, Aliza (2007). Blood and Belief: The PKK and the Kurdish Fight for Independence. NYU Press. p. 191. ISBN 978-0-8147-5711-6.

Further reading

- Kaminaris, Spiros Ch. (June 1999). "Greece and the Middle East". Middle East Review of International Affairs, Vol. 3, No. 2.

- Özcan, Ali Kemal (2005). Turkey's Kurds: A Theoretical Analysis of the PKK and Abdullah Ocalan. London & New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-36687-9.

- Parkinson, Joe, and Ayla Albayrak (15 March 2013). "Kurd Locked in Solitary Cell Holds Key to Turkish Peace". The Wall Street Journal (archived copy).

External links

- Abdullah Öcalan

- 1949 births

- Living people

- 21st-century philosophers

- 21st-century Kurdish writers

- Ankara University Faculty of Political Sciences alumni

- Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights

- Article 5 of the European Convention on Human Rights

- Article 6 of the European Convention on Human Rights

- Former Marxists

- Istanbul University Faculty of Law alumni

- Kurdish communists

- Kurdish feminists

- Kurdish male writers

- Kurdish revolutionaries

- Kurdish socialists

- Kurdistan Communities Union

- Male feminists

- Members of the Kurdistan Workers' Party

- Öcalan family

- People barred from public office

- People extradited from Kenya

- People extradited to Turkey

- People from Halfeti

- People imprisoned on terrorism charges

- Prisoners sentenced to death by Turkey

- Prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment by Turkey

- Socialist feminists

- Turkish Kurdish politicians

- Turkish people imprisoned on terrorism charges

- Turkish people of Kurdish descent

- Turkish-language writers

- Political prisoners in Turkey

- People convicted of treason against Turkey